Gardens of Paradise

Without doubt, the gardens of paradise are the ultimate utopias of Muslim consciousness. But what does the Qur’an say about gardens, landscapes and the promise of paradise? In this essay, I give longer extracts from the Qur’ān, to show the context in which garden or nature imagery are used in that text, and to trace those images and expressions back to the natural landscape of the area in which that text was revealed, the history of agriculture and the social use of gardens before the rise of historical Islām in the seventh century. My aim is to sketch the sort of landscape and agricultural practices and horticultural models that informed the Qur’ānic vision, with the essential caveat that the Qur’ān is a religious and moral text, not a manual of gardening, and that any reference it makes to “realia” is by and large metaphorical, striking similes and exempla (āya / āyāt, mathal / amthāl) for the edification of the faithful.

The longue durée - the survival over hundreds of years, if not millennia, of historical echoes persisting over time, embedded in landscape or language, in typical significant gestures, modes of visual representation, lexical items, legends, folklore or proverbs - is apparent in the Qur’ān text, and places that revelation firmly within the context of the historical cultures that flourished between the Nile valley and Mesopotamia, Yemen and Syria over the course of two millennia before the great Arab conquests of the mid seventh century. These cultures are indebted not only to the continuing self-conscious tradition of Jewish and Christian lore, but also to the chronologically and geographically more distant models from the Eastern Mediterranean, Egypt and Babylon, as well as Assyria and Irān. It remains to disentangle elements that are observed within the Hijāz or the Arabian Peninsula from those that have been incorporated along with the stock of inherited stories and exempla from further afield. In any case, the extrapolation of detail regarding gardens must be done with caution and humility: there is always a danger of over- or mis-interpreting textual evidence.

The Semitic area provides the geographical frame of reference for the Qur’ān, with its geology apparent on the surface with bare rocks, volcanic lava flows, stony and sandy deserts, its precarious hydrology with occasional oases and seasonal water courses and few, crucial rivers, and its hot arid climate and progressive desertification. The Hijāz, rocky and infertile Mecca and the oasis Madina, the volcanic Harra, the fertile strip of the Wādi al-Qurā, the oases in Najd and towards the eastern coast at al-Ahsā and Qatif , and in the north at Hā’il, are the core of the Qur’ānic culture of the Arabian Peninsula. Further afield, the fertile Yemen highlands and the Tihāma coastal strip, and the great valley of the Hadramaut to the south, the Jordanian, Palestinian and Syrian landscape of desert and oases and cultivated areas in the Fertile Crescent to the north feed into the culture of the Qur’ān. Further still, the Egyptian balance of Nile and desert and the Delta, Mesopotamia, Babylon, Assyria, and – on the remotest horizon - the Irānian plateau, the Mediterranean, the Horn of Africa and Ethiopia where the first Muslim refugees sought sanctuary before the Hijra of 622 – all these are relevant to the world-view and range of geographic and cultural reference of the Qur’ān.

The invention of agriculture, hoeing by hand, ploughing with oxen, cereal cultivation, date palm groves, grapes and the making of wine, salad and herb gardens; irrigation by wells, canals, flash-flood control, managing and maximising the benefits of rainfall or snow-melt; the invention of land-surveying; improving soil quality, minimising erosion or invasive sand; pollinating date palms, sowing grain seeds; the domestication of animals; the exploitation of ecological niches of seasonal verdure by transhumance; the interdependence and mutual exchange and frequent rivalries between settled agriculturalists and nomad pastoralists : all these developments underlie the stories and lessons of the Torah and the Qur’ān. The need of agriculturalists for fixed and regular calendars, established by observation of the movements of sun and moon, and attempts at foretelling the future by observing the 12 signs of the zodiac and the movements of the seven known planets, the tendency to conciliate the elements and life forces in the form of a multiplicity of divinities; the more egalitarian warrior ethos of the nomads and their keen awareness of the night sky : all this underlies much of the teaching and poetic language of the texts of revelation.

What are gardens for? How did they originate? Do they cease to be gardens when they become too big? In what sense are the accidental geometries of a surveyed and demarcated or irrigated agricultural landscape different from the intentionally and aesthetically-planned geometries of formal gardens? These are all questions that must be asked in the attempt to elucidate the concept and typology of gardens implicit in the Qur’ānic revelation. Reference must be made to a possible origin of gardens in sacred groves, with their taboos on cutting down trees or hunting animals, with their shade, mystery and symbolism; but also to the more mundane domestic vegetable and herb patch adjacent to dwellings in towns and villages, the sphere of women as nurturers and cooks; at a level of greater social elaboration and magnificence are formal gardens for receptions, parks for hunting and sport, and the typical combination of later Islāmic culture, the royal enclosures of gardens with walkways, kiosks, palaces giving privacy, views, shade, water, coolness in the heat of the summer, as palace complexes. As noted by Ibn Khaldun, the nomad origin of warrior and aristocratic elites of the Islāmic world guarantees the importance of tents as a relic of nomadism - well suited to the climate - which is scarcely diminished even in the modern era. The tent can have one or all of its sides raised and opened to the breeze and the view, and this aesthetic of lightness and openness has influenced the style of construction of garden pavilions and kiosks through most of Islamic architectural history.

In Sura al-An’ām VI, āya 95 – 99, we read:

“Inna Llāha fāliqu l-habbi wa n-nawā ... la āyātin li qaumin yu’minun”

In A J Arberry’s translation (The Qur’an Interpreted), which I have used throughout:

“It is God who splits the grain and the date-stone, brings forth the living from the dead; He brings forth the dead too from the living. So that then is God; then how are you perverted? He splits the sky into dawn, and has made the night for a repose, and the sun and moon for a reckoning. That is the ordaining of the Almighty, the All-knowing. It is He who appointed for you the stars, that by them you might be guided in the shadows of land and sea. We have distinguished the signs for a people who know. It is He who produced you from one living soul, and then a lodging place, and then a repository. We have distinguished the signs for a people who understand. It is He who has sent down out of heaven water, and thereby We have brought forth the shoot of every plant, and then We have brought forth the green leaf of it, bringing forth from it close compounded grain, and out of the palm-tree, from the spathe of it, dates thick-clustered, ready to hand, and gardens of vines, olives, pomegranates, like each to each, and each unlike to each. Look upon their fruits when they fructify and ripen! Surely in all this are signs for a people who believe.”

This extended passage, a beautifully observed evocation of nature and agriculture, is a typical example of the use of natural imagery in the Qur’ān to emphasise God’s power as creator of all life and life-forms; and to underline the doctrine of the resurrection as an essential part of the faith. From the smallest seed to the furthest star, the natural order ideally serves mankind, and the life-giving quality of water, coming as rain from heaven, recalls God’s practical mercy to His creature Mankind; the landscape evoked is in strong contrast to the black calcined lava-flows of the Harra or the sandy and stony deserts of Najd, rather it is one of arable fields of cereals, date-palm groves, vineyards, olive groves, gardens of pomegranates: an agricultural landscape, made fruitful by the cooperation of husbandry and ever-renewed creation, a transparent message to those with eyes to see and ears to hear.

As in any literary or artistic representation, there are highlights: choices are made in this text. It is an evocation for the purposes of orally delivered spiritual and moral lessons, not an exhaustive seed-catalogue or farmer’s manual. It is a moot point where the olive zaitun, olive oil zait, the vine karma, grapes a’nāb, and the pomegranate rummān, grow best – do these plants represent some Eastern Mediterranean location north of the Hijāz? Syria was a major exporter of olive oil during the Roman Empire, as testified by the many “dead cities” around Aleppo.

The germination of seeds, as a miracle of renewed life after apparent death, a symbol of the resurrection, has recently been shown to be possible even after 2,000 years lying dormant, in the case of cereal grains buried in the palace of Herod at Masada. This helps elucidate the twelfth century Persian mathematician ‘Umar Khayyām’s sceptical quatrain, calling into doubt the reality of heaven and the resurrection: “Would that there were a place to rest, or a destination to reach on this distant road, or that, after a hundred thousand years in the belly of the earth, like wheat-grass, we might hope to spring up once again!”

The sceptical materialist view of life is briefly encapsulated in the Qur’ān, sura al-Jāthiya XLV, āya 24: “They say, there is nothing but our present life; we die, and we live, and nothing but Time destroys us.” The tyranny of time, identified as Zurvān by the Sāsānian Irānian Zoroastrians, dominates even the gods, the forces of good and evil; this dahri heresy, denying divine agency or the resurrection and life after death, was the reductionist materialist hopelessness against which, as also against polytheism, the preaching of the Qur’ān was addressed, insisting on the absolute power of the one transcendent creator God, and the reality of resurrection and judgement. The Book of the Prophet Ezekiel (chapter 37 “and shall these bones live?”) is echoed in the heart of the Qur’ān, sura Yā Sin XXXVI, āya 78 – 83:

“Qāla man yuhyi l-‘idāma wa hiya ramim? Qul yuhyi-hā l-ladhi ansha’a-hā awwala marratin ... al-ladhi bi yadi-hi malakutu kulli shai’in wa ilai-hi turja’un”

“He says, ‘Who shall quicken the bones when they are decayed?’ Say: ‘He shall quicken them who originated them the first time; He knows all creation, who has made for you out of the green tree fire and lo, from it you kindle.’ Is not He, who created the heavens and the earth, able to create the like of them? Yes indeed; He is the All-creator, the All-knowing. His command, when He desires a thing, is to say to it ‘Be’ and it is. So glory be to Him, in whose hand is the dominion of everything, and unto whom you shall be returned.”

The cultivation of date-palms nakhla is as old as civilization throughout the hot and arid areas of the Arabia , North Africa and the Middle East, wherever irrigation is to be had. There is a beautiful Hadith commanding respect for the date palm, to be treated as “family” as it was created of the same clay as Adam. But in the Sira, the biography of the Prophet, as recorded in the Hadith, there is also the incident of the prohibition of artificial pollination of date-palms, until the ensuing sterility threatened to bring famine. Like types of cereals that need human cooperation to flourish, dates are best produced with human help in pollination of the female palms, which is only marginally more extraordinary than pollination by bees, moths, flies or bats. The Prophet’s initial scruples about apparently unnatural interference with the divine processes of nature gave way to the professional expertise of the agriculturalists, in realism and humility, the Prophet acknowledging “I am just a man like you”. The words tamr or rutab or ‘ajwa for dates fresh or dry feature frequently in Qurān, Hadith and Sira, for example in the Hadith (Bukhāri chapter of foods 63, section 15) of breaking fast with seven dried dates as a recommended diet. Dates were the main sweetener along with honey and figs tin, before the introduction of cane sugar after the great Islamic conquests of the seventh century. Techniques such as supporting plants on trellises or columns, such as the vine karma and grapes ‘anab, plural a’nāb, are referred to in the Qur’ān, sura al-An’ām VI, āya 141 ma’rushāt, as can still be seen today with short stone columns in Yemen to support vines for the production of eating grapes and dried raisins.

Hadiqa plural hadā’iq, an enclosed garden, occurs only three times in the Qur’ān, always in the plural, as in sura ‘Abasa LXXX, āya 24 – 32:

“Fa-l-yanzuri l-insānu ... wa li-an’āmi-kum”

“Let Man consider his nourishment. We poured out the rains abundantly, then we split the earth in fissures and therein made the grains to grow and vines, and reeds, and olives, and palms, and dense-treed gardens, and fruits and pastures, an enjoyment for you and your flocks”

Jannat is the most frequently used word for a garden, orchard or an oasis in the Qur’ān; the word is Aramaic in origin, already present in the Torah, in the Book of Genesis’s account of the creation of the “Garden” of Eden, which was not so much a small enclosed garden space, but rather an extensive area of cultivation, even a microcosm of the known world; the word is also attested in the Gospel account of the “garden” of Gesthemane; also in Ethiopic names, such as the church of Genneta Maryam near Lalibela; also in Sabaean inscriptions of South Arabia, including a fine Minaean bronze plaque from the temple of Wadd in Qaryat al-Faw, where the site is referred to as Gannatun, the oasis. The proof case, where textual reference in the Qur’ān can be checked against the physically surviving archaeological record is in the account of Sabaean irrigated agriculture and the final destruction of the dam at Ma’rib, the ceremonial capital of Sabā in Yemen.

“laqad kāna li-Sabā’i fi maskani-him āya: jannatāni ‘an yaminin wa shimāl ... wa athlin wa shai’in min sidrin qalil”

“For Sheba (Sabā) also there was a sign in their dwelling place – two gardens, one on the right and one on the left: ‘Eat of your Lord’s provision, and give thanks to Him; a good land, and a Lord All-forgiving.’ But they turned away; so We loosed on them the Flood of ‘Arim, and we gave them in exchange for their two gardens two gardens bearing bitter produce and tamarisk bushes (athl) and here and there a few lote-trees (sidr, Zizyphus Spina Christi, jujube)”.

The notable dam at Ma’rib, and its two irrigated areas of oases north and south of the torrent bed, can be used as a reality check for the use of the word jannat in the Qur’ān and elsewhere. The usual translation of the word jannat as “garden”, or here the dual form jannatān as “two gardens”, is rather overtaxed as a description of 10,000 hectares of irrigated, cultivated land, or 5,000 hectares per “garden”; it is more adequately translated as oases, irrigated cultivated areas - unless “garden” is used in a specific sense, such as the English counties Kent or Herefordshire being described as the “garden of England” because of their many apple orchards; certainly this use of “garden” is far from any concept of landscape architecture or formal garden design.

The ancient civilizations of Arabia Felix, South Arabia, the Yemen, the blessed land, were based on trade networks dealing mainly in aromatics and gum incenses collected wild, and on a thriving agriculture characterised by extremely skilful terracing and irrigation to maximise the agricultural potential of often marginal lands in the mountains or on the edge of the desert. Whereas the mountains to the West attracted the remnants of monsoon rains, and gave rise to an extraordinary system of terraced agriculture, the land further East, as the landmass of Arabia shelves down towards the Gulf and flattens out, is more arid. In order to support food production for their capital city Ma’rib, situated on the edge of the Rub’ al-Khāli desert, the Sabaeans had to harness the spate of twice yearly rains from the surrounding mountains and channel them to the productive land north and south of the torrent of Wādi Dhana, as it emerged from the limestone mountains of the Jabal Balaq. A remaining sluice gate of the old dam of Ma’rib dates from almost 3,000 years before the present, and the first Sabean inscriptions date from the mid-eighth century BC; the kingdom grew to its greatest strength under Karrib’il Watar around 685 BC when he conquered Najrān, ‘Aden, and the Tihāma. Both the northern ‘Arab nomad migrations of the second century BC, and the growth of the new power of Himyar which had its capital further west in the mountains at Zafar, caused a gradual decline of the state of Sabā. Ma’rib remained, however, an important ceremonial centre, and attempts were made to counteract the effects of silting, up to 30 metres deep upstream from the dam, and those of ruptures in the dam walls. The rise of Judaism and Christianity in the area led to a decline of the great pagan temples that had coordinated regular irrigation maintenance and repair. The last inscriptions recording attempted repairs to the dam date to 549 under the rule of the Ethiopian conquerors of the Yemen and their viceroy Abraha. Thereafter, uncontrolled silting and flash-flood damage destroyed the central masonry-clad earthwork barrage but left standing the north and south sluice-gates and diversion channels, built directly onto the rock, of solid, beautifully cut masonry. Whereas these had, at their peak, channelled up to two million cubic metres of water annually during the spate, and had irrigated up to 10,000 hectares and fed a population of up to 50,000, the land now reverted to semi-desert of acacia and tamarisk scrub (athl, sidr); and the population migrated to San’ā. This was finally the case after almost one and a half millennia – an impressive record for a masonry-clad earthwork barrage coping with a huge annual accumulations of silt: the Sail al-‘Arim, the seventh century flood, swept away the working dam.

Another destruction is recorded in the Qur’ān, sura al-Fajr LXXXIX, āya 6 – 8: “Hast thou not seen how thy Lord did with Ād, Iram of the pillars, the like of which was never created in the land?” Iram, the legendary lost garden, with pillars dhāt al-‘imād clearly also belonging to the south of Yemen or the Hadramaut, where the grave of their Prophet Hud is still venerated. In the Qur’ān, it actually refers more to a former city-state on the incense route, destroyed and abandoned, and thus an example of the precariousness of human civilisation, exposed to the blasts of fate and divine displeasure. There were historical reasons too for such decay: the economic near-collapse of the Roman Empire, major importer of Yemeni incense to burn on its temple altars, in the fourth century; the development of the maritime route up the Red Sea for oriental luxury trade, which rendered the camel-borne trade across the Arabian deserts too slow, expensive and dangerous; the Ethiopian invasion of the Yemen in the sixth century to avenge the martyrdom of the Himyarite Christians of Najrān at the hands of an Arab king converted to Judaism; the destructive wars of the early seventh century between Heraclius of Byzantium and Khusrau / Chosroes of Irān, which ravaged Syria and severely weakened both empires, while establishing a Persian hold on Yemen and Omān. But the romantic allure of the doomed city and its gardens gripped the later imagination, with the result that the name Iram has been given to many later gardens, notably the beautiful garden of the nineteenth century Qashqāi tribal chiefs, now the Botanical Institute of Shirāz University in Fārs, Irān.

Caution should also be applied in dealing with the Garden of Eden: the text in the Book of Genesis has “God planted a garden in Eden in the east”, Eden being a larger place than the “garden” and the name echoing the South ‘Arabian port of ‘Aden – though that particular calcined waste of volcanic lava hardly evokes the land of pleasure, which is what Eden means! Jannat ‘ adn is a place of pleasure, paralleled by jannat al-na’im delight in another common Qur’ānic compound for the paradise garden; or by jannat al-firdaus, paradeisos, pardis – a large royal hunting enclosure, the Persian word referring to the enclosed hunting grounds or paradises of the ancient Persian kings, whose empire included the southern portions of the Arabian peninsula until the seventh century. All these Qur’ānic compounds are expressed typically as jannat ‘adn, jannat al-na’im, jannat al-firdaus, and also jannat al-ma’wā, the garden of eternal abode; whereas the formulation with rauda, plural riyād / raudāt, is raudāt al-jannāt (Qur’ān sura al-Shurā XLII, āya 22) a green area which can also be a wide expanse for cavalry exercises and other sports; later, rauda was also applied to funerary gardens, notably the Prophet’s tomb in his mosque, originally built with the palm-tree columns in the courtyard of his house in Yathrib / Medina. The Qur’ānic compounds are used more or less interchangeably, as indeed are singulars and plurals.

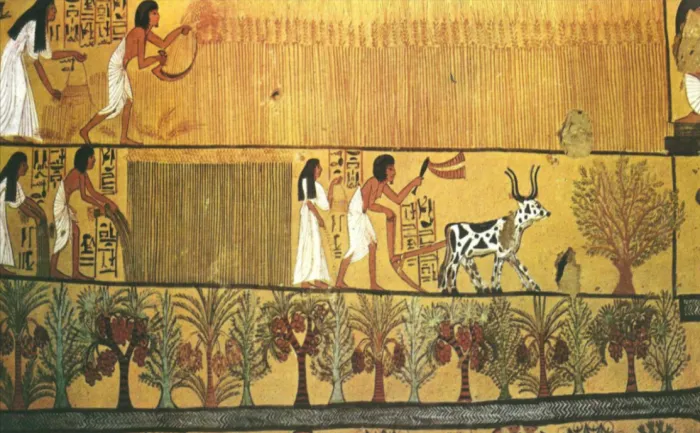

The most frequently repeated phrase descriptive of the Qur’anic paradise, contrasted with the apocalyptic ending of the world and the torments of Hell, is in Qur’ān sura al-Baqara II, āya 25, and passim, “gardens underneath which rivers flow”. Precisely what that means is not always clear, especially when a similar phrase is used about rivers flowing beneath buildings as in Qur’ān, sura al-Zumar XXXIX, āya 20. Are they small irrigation channels of water flowing through palm grove oases, or larger rivers, as the Barada at Damascus flowing below tower houses scattered through orchards and parkland, as depicted in the famous Umayyad mosaics of the Great Mosque? There is however a distinct, if distant, reminiscence in this phrase of the early Egyptian paradise, the fields of peace or of Yaru / Ialou, which are entirely surrounded by water, as in the thirteenth century BC depictions of agriculture and gardens as a setting for the afterlife in the Tomb of Sennejem, Dair al-Madina, Luxor, Egypt.

Sennejem, a craftsman for the royal tombs, lived and was buried in the craftsmen’s village, and is shown with his wife, in their finest clothes, working in the fields of paradise, the fields of Yaru / Ialou: this agricultural landscape is surrounded and intersected by flowing water canals drawn off the Nile. The lower levels show water plants such as papyrus, then date palms and doum palms, then persea and sycamore fig, then a scene of the blessed departed ploughing with oxen, sowing seed, pulling flax and harvesting tall-standing wheat before sailing to meet the gods.

Agricultural work in the afterlife is another Egyptian echo in the Book of Genesis account of Eden (chapter 2, verse 15) where the first man is put to work in the garden, in order not to sit eternally idle. This is also echoed in the Hadith recounted by Abu Huraira in Bukhāri’s collection the “Sahih” (chapter 61 section 20), which seems to echo some disquiet with the apparent idleness of the feasting dear departed in the Qur’ānic paradise: “One of the inhabitants of Paradise asked his Lord permission to plough and sow seed. ‘Do you not have all that you desire?’ ‘Yes, but I would like to start sowing.’ So he sowed, and in the blinking of an eyelid, the plants grew and ripened, giving a mountainous harvest. ‘O son of Adam, nothing will satisfy you!’ An Arab nomad listening to the Prophet exclaimed ‘That must have been one of the Quraish or a Helper from Medina – these oasis- dwellers like ploughing and sowing, whereas we nomads have nothing to do with agriculture!’ And the Prophet laughed.”

Many other fragments of visual evidence survive to inform us about the ancient Egyptians’ attitudes to and practice of agriculture and horticulture: the fifteenth century BC temple of the female Pharaoh Hatshepsut at Dair al-Bahri shows the transport of incense trees, with their roots encased in their original soil, all the way from the land of Punt (Somalia or East Africa), by ship back to Luxor – the avenue to the temple still shows the holes where these trees were planted. The Temple of Karnak has a courtyard with linear bas-reliefs of a variety of mostly Near Eastern plants, currently known as the “Botanic Garden”, deriving from the military campaigns of Thutmose III in Palestine, also fifteenth century BC. The early fourteenth century BC tomb of the scribe Menna shows the land being surveyed and measured to estimate the cereal crop for taxation. Nearby, the tomb of Immenenheb shows a rectangular orchard planted with 3 concentric alignments of 32 sycamore fig trees, 24 date and doum palms, and 20 perseas, with a rectangular lotus pool in the centre; this is similar in design to the now destroyed floor painting at al-Amarna recorded by Petrie, where the rectangular pool was surrounded by concentric beds of flowering plants. Among the most striking instances of Egyptian survivals into the Biblical canon, and thence recognisably into the nature imagery of the Qur’an, is the version of Akhenaten’s hymn of praise to the Aton, the unique solar divinity, the first historically attested monotheism of circa 1350 BC, which appears as Psalm 104:

“My God, how great you are! Clothed in majesty and glory, wrapped in a robe of light! You stretch the heavens out like a tent, you build your palace on the waters above; using the clouds as your chariot, you advance on the wings of the wind; you use the winds as messengers and fiery flames as servants. You fixed the earth on its foundations, unshakeable for ever and ever; you wrapped it with the deep as with a robe, the waters overtopping the mountains. You set springs gushing in ravines, running down between the mountains, supplying water for wild animals, attracting the thirsty wild donkeys; near there the birds of the air make their nests and sing among the branches. From your palace you water the uplands until the ground has had all that your heavens have to offer; you make fresh grass grow for cattle and those plants made use of by man, for them to get food from the soil: wine to make them cheerful, oil to make them happy and bread to make them strong. You made the moon to tell the seasons, the sun knows when to set: you bring darkness on, night falls, all the forest animals come out: savage lions roaring for their prey, claiming their food from God. Earth is completely full of things you have made: among them vast expanse of ocean, teeming with countless creatures, creatures large and small, with the ships going to and fro. All creatures depend on you to feed them throughout the year; you provide the food they eat, with generous hand you satisfy their hunger. You turn your face away, they suffer; you stop their breath, they die and revert to dust. You give breath, fresh life begins, you keep renewing the world. Glory for ever to God! May God find joy in what He creates, at whose glance earth trembles, at whose touch the mountains smoke!”

Other Egyptian survivals are the victor’s characteristic gesture of taking his defeated foe by the forelock, so often seen on Egyptian bas-relief sculpture from the 5,000 year-old palette of Narmer onwards, and echoed in the Qur’ān’s account of God taking the sinner by the forelock nāsiya plural nawāsiy, in Qur’ān sura al-Rahmān LV, āya 41: “The sinners shall be known by their mark, and they shall be seized by their forelocks and their feet”. The recurring phrase “He makes the night to enter into the day and makes the day to enter into the night”, as for example in Qur’ān sura al-Fātir XXXV, āya 13, can be understood as referring to the lengthening of the hours of daylight during the summer and the lengthening of the hours of darkness during winter against the ideal standard of equal duration of each (day and night) in traditional Egyptian time-keeping.

Archaeo-botany has allowed the identification of many plants, especially food plants from ancient Egypt, including peas, beans, lentils, onions, garlic, leeks, radishes and cucumbers – thus confirming the Torah’s Book of Numbers (chapter 11, verse 5) “We recall the fish that we used to eat in Egypt for free, the cucumbers, the watermelons, the green leeks, the onions, and the garlic!” and Qur’ān sura al-Baqara II, āya 61: “Pray to the Lord for us that He may bring forth for us of that the earth produces – green herbs, ridged cucumbers, corn, lentils, onions”. These are accounts of the regrets of the wandering Israelites on their long – 40 year - trek from well-fed Egyptian captivity through the deserts with its divine but unvarying diet of manna. An after-echo of Egypt’s reputation for fertility is the lovely mosaic preserved at Palestrina in Italy, showing the lush landscape of the Nile Delta.

Many edible plants and vegetables have names going back to ancient Babylon and its ancient Semitic Akkadian texts, some from over 3,500 years before the present – many are preserved in modern Semitic languages such as Arabic: na’nā’ mint; kuzbara coriander; kammun cumin; thum garlic; simsim sesame; kam’a desert truffle; karma vine; as well as other words to do with eating such as: akl food; samn clarified butter; arnab hare; nun fish; dam blood; mā water; tannur clay oven. If language can have such a long memory, it is not surprising that gesture and visual culture can also present continuities over many hundreds of years.

Qur’ān Sura al-Rahmān LV, āya 46 – 78:

“Wa li man khāfa maqāma rabbi-hi ... dhi l-jalāli wa l-ikrām”

“But such as fears the Station of his Lord, for them shall be two gardens – O which of your Lord’s bounties will you and you deny? abounding in branches – O which of your Lord’s bounties will you and you deny? therein two fountains of running water – O which of your Lord’s bounties will you and you deny? therein of every fruit two kinds - O which of your Lord’s bounties will you and you deny? reclining on couches lined with brocade, the fruits of the garden nigh to gather – O which of your Lord’s bounties will you and you deny? therein maidens restraining their glances, untouched before them by any man or jinn – O which of your bounties will you and you deny? lovely as rubies, beautiful as coral – O which of your Lord’s bounties will you and you deny? Shall the recompense of goodness be other than goodness? O which of your Lord’s bounties will you and you deny?

And besides these shall be two gardens – O which of your Lord’s bounties will you and you deny? green, green pastures – O which of your Lord’s bounties will you and you deny? therein two fountains of gushing water – O which of your Lord’s bounties will you and you deny? therein fruits and palm-trees and pomegranates – O which of your Lord’s bounties will you and you deny? houris, cloistered in cool pavilions – O which of your Lord’s bounties will you and you deny? untouched before them by any man or jinn – O which of your Lord’s bounties will you and you deny? reclining upon green cushions and lovely druggets – O which of your Lord’s bounties will you and you deny?

Blessed be the Name of thy Lord, majestic and splendid”

This richly ornate passage, in hypnotically beautiful Arabic, is an extended example of the other most typical and frequent use of nature imagery in the Qur’an, to evoke the timeless and ineffable bliss of the afterlife in paradise. It is one of the texts most often quoted about Islamic gardens, paradise conceived in terms of a series of “gardens”, graded according to the merits of the blessed. The first two gardens are orchards of fruit trees with thick canopies of branches filtering the light, and with springs of water channelled into runnels and rivulets irrigating the ground; in this setting are placed rich textiles, carpets and cushions, where the blessed recline to take their ease with complaisant virginal girls. The other two gardens are interspersed with pavilions or tents among the trees, which promise the delights of yet more virginal girls reclining on more rich textiles awaiting the dear departed.

The mention of the garden “abounding in branches” calls to mind Roman gardens, such as the frescoed room representing the Empress Livia’s garden arboretum, now in the Roman Museum, Rome, with exotic imported trees, fountains and birds and enclosure of trellis fences – though this is a different tradition of gardening, with the pedestal fountains and jets of water implying a level of sophistication not discernible in the Qur’an’s account of paradise gardens.

Qur’ān, sura al-Wāq’ia LVI, āya 10 – 40:

“Wa s-sābiqun as-sābiqun: ulā’ika l-muqarrrabun ... wa thullatun min al-ākhirin”

“And the Outstrippers: the Outstrippers, those are they brought nigh the Throne, in Gardens of Delight (a throng of the ancients, and how few of later folk) upon close-wrought couches, reclining upon them, set face to face, immortal youths going round about them with goblets and ewers, and a cup from a spring (no brows throbbing, no intoxication) and such fruits as they shall choose, and such flesh of fowls as they desire, and wide-eyed houris as the likeness of hidden pearls, a recompense for that they laboured. Therein they shall hear no idle talk, no cause of sin, only the saying ‘Peace, Peace!’

The Companions of the Right (O Companions of the Right!) mid thornless lote-trees and serried acacias, and spreading shade and outpoured waters, and fruits abounding unfailing, unforbidden, and upraised couches. Perfectly We formed them, perfect, and We made them spotless virgins, chastely amorous, like of age for the Companions of the Right. A throng of the ancients and a throng of the later folk.”

Here, the previous account of heavenly bliss is further clarified and elaborated in the grading of paradise gardens according to the merits of the deceased, and the divine garden party is furnished with ever more elaborate paraphernalia of royal entertainments: bejewelled young wine-servers (Arberry’s ”immortal” chooses the association with khuld rather than to catch the specific association of mukhalladun with khilda, precious stones, as pointed out by the French translator of the Qur’ān, Jacques Berque), the guests reclining on luxurious couches as in a classical symposium or Assyrian or Persian royal feast. Couches or benches or takht or charpoy – arika plural arā’ik or sarir plural surur - were used to express royal or aristocratic ease out of doors in parkland or palm grove, as can be seen as far back as the Nineveh bas-reliefs.

An Assyrian bas-relief from Nineveh (circa 645 BC) (now in the British Museum Assyrian basement) shows date-palms and vines and the king Ashurbanipal on a couch and his queen on a throne, each ceremonially drinking out of a shallow bowl in one hand, holding a flower in the other hand, to the sound of music This prefigures the Qur’ān’s promise of the blessed departed reclining on couches, attended by young wine servers and virginal girls - BUT not the shrivelled head of the Elamite king killed in battle some 12 years previously, hanging upside down in the pine-tree, which is more in accord with Assyrian blood-thirstiness than with the Qur’ān’s promise of mercy. The servants with fly-whisks, the incense burners, garland necklace, rich textiles and bolsters, palm-trees and vine arbour hung with bunches of grapes close at hand, birds flitting between the trees, altogether could be a foretaste of the Qur’ānic paradise. That imagery is ultimately based on such royal precedents, which were perhaps known in C7th Arabia in the form luxury Sāsānian silver imported from Irān which often showed similar feasting – it should be remembered that the Sāsānian Irānians ruled the Yemen and Omān until the great ‘Arab conquests of the mid seventh century. In the Qur’ān this imagery is not literal description, but is used to give an intimation of the ineffable bliss of the afterlife.

The paradisiac party is different in that that there are no headaches or brawls or vulgarity such as are too often caused by alcohol at worldly parties. Fresh fruit and roasted game birds or chickens accompany the drinking, with, again, the virginal girls ready to pleasure the dear departed. The idealised nature of this imagery is evident in the sufficient space enjoyed by each of the facing couches, which could, if realistically described, become a cause of over-crowding worse than a summer beach full of deck-chairs or a coach-park or a supermarket parking lot ... luckily such prosaic considerations do not seem to have exercised the poetic genius of the Qur’an.

Qur’ān, sura al-Insān LXXVI, āya 5 -22:

“Inna al-abrāra yashrabuna min ka’sin ... wa kāna sa’iu-kum mashkur”

“Surely the pious shall drink of a cup whose mixture is camphor, a fountain whereat drink the servants of God, making it to gush forth plenteously. They fulfil their vows, and fear a day whose evil is upon the wing; they give food, for love of Him, to the needy, the orphan, the captive: ‘We feed you only for the Face of God; we desire no recompense from you, no thankfulness; for we fear from our Lord a frowning day, inauspicious.’ So God has guarded them from the evil of that day, and has procured them radiancy and gladness, and recompensed them for their patience with a Garden, and silk; therein they shall recline upon couches, therein they shall see neither sun nor bitter cold; near them shall be its shades, and its clusters hung meekly down, and there shall be passed around them vessels of silver, and goblets of crystal, crystal of silver that they have measured very exactly. And therein they shall be given to drink a cup whose mixture is ginger, therein a fountain whose name is called Salsabil. Immortal youths shall go about them: when thou seest them, thou supposest them scattered pearls, when thou seest them then thou seest bliss and a great kingdom. Upon them shall be green garments of silk and brocade; they shall be adorned with bracelets of silver, and their Lord shall give them to drink a pure draught. ‘Behold, this is a recompense for you, and your striving is thanked.’”

Wine tempered with camphor – an Irānian royal taste, which a modern oenophile might regard with dismay! A ginger-flavoured drink is more enticing. Sura al-Wāqi’a LVI, āya 89 adds “fa rauhun wa raihānun wa jannatu na’imin” which Arberry translates as “There shall be repose and ease and a Garden of Delight”, which fails to catch the additional sensory delight of fragrant herbs “raihān” normally identified as sweet basil. These are among the very few allusions to taste and smell in the Qur’ān, whereas the Prophet’s love of perfumes was almost a leitmotif of Hadith and Sira literature, as was his love of the colour green, and of honey, especially from Wādi Du’ān in the Hadramaut.

The comparison to hidden pearls, applied both to virginal girls, houris, and to young wine servers, ghilmān, allows us to interpret more closely the non-figural mosaics of the Damascus mosque which are the most important surviving depictions of landscape – probably paradisiac – from the early imperial phase of Islāmic civilization.

In the year 70, the Umayyad Caliph al-Walid, son of the Caliph ‘Abd al-Malik, had the Great Mosque at Damascus, formerly a temple and a church, rebuilt and redecorated with mosaics. The decoration was carried out by mosaicists sent by the Byzantine Emperor from Constantinople, and they worked under the norms of Islam: no human or animal figures were shown. According to al-Maqdisi, in his geographical work Ahsan al-taqāsim fi Ma’rifat al-aqālim in the chapter Iqlim al-Shām, describing Syria and its capital Damascus, specialised craftsmen were summoned from Fārs, India, the Maghreb as well as Rum (Byzantine Anatolia) for the building campaign and the expenditure on the Great Mosque was equivalent to 7 years’ taxation revenue of the whole of Syria, not counting the 18 shiploads of gold and silver from Cyprus, and the Byzantine Emperor’s gift of mosaic tesserae. This extraordinary expense was justified as propaganda in a land whose extant Christian monuments still aroused the wonder of all travellers: but after the building of the Great Mosque, Muslims too could boast of possessing one of the wonders of the world. Among the gateways leading into the great courtyard was one significantly called Bāb al-Faradis the gate of paradise; the portico surrounding the courtyard had its walls covered with a dado of marble and above that with mosaics up to the roof; the mihrāb was adorned with encrustations of carnelian and turquoise, and was surmounted by a great dome. The extensive fragments of mosaic surviving today on the west wall of the portico show, in a cool palette of blues, greens and gold, landscapes of large trees and streams flowing beneath them, and pavilions with pearls hanging in the doorways: a visual allusion perhaps to the beautiful girls and boys of paradise who are like hidden pearls, in attendance to gratify the blessed departed – the Islamic prohibition of figural representation, inherited from Judaism, encourages a poetic and metaphorical reading of the landscape buildings and of the pearls in their door-frames. The types of building shown could be said to correspond to the open pavilions, tower houses, palaces (khiyām, ghuraf, qusur) mentioned repeatedly in the Qur’ānic descriptions of paradise. In a Hadith from the collection of Bukhāri (chapter 81, section 53, number 6), the Prophet is quoted as saying “As I was walking in paradise, I came across a river, which had along each of its banks, domed pavilions qubba made of huge hollowed out pearls. I asked the Angel Gabriel, who said ‘This is the River of Plenty Kauthar’”

There is nothing in the passages quoted above, to justify anachronistic back-projection onto the Qur’ān text of geometrically formal garden designs of avenues and parterres and fountains with water jets of the late medieval and early modern gardens of Islāmic Irān and India and Spain. There are certain themes that do emerge from the text of the Qur’ān itself – the miracle of creation and of growth, the danger of sudden natural disasters, the thirst for peace, safety, cool shade and running streams as a relief from the relentless day-time heat and night-time cold and ever-present dangers of the desert, a highlighting of certain plants and fruits: but it is all much closer to a utilitarian market garden and fruit orchard and date-palm grove than to a picturesque garden organised solely or principally for visual delight. Delight is present, the promise of sensual love, picnics, drinking parties that leave no headaches, conversation that is always stimulating, never dull or boorish, rich furnishings, couches, textiles of green silk and brocade, table-ware of silver and crystal, ever-youthful and complaisant wine servers and virginal houris – but this delight takes place in an outdoor space that is shaped by the needs of agriculture rather than by those of strictly geometrical, architecturally planned and designed horticulture. The formality of some aspects of the social use of gardens / oasis plantations is not paralleled by formality of design until well after the period of the revelation of the Qur’ān: still today, a rural host will open the wooden gate in the mud-walled orchard or palm grove, pull up a wooden bench-bed takht or chārpoy, place it under the shade of fruit trees or date palms, perhaps over an irrigation channel or near a spring of cool water, and, covering the takht with a pile rug and bolster cushions, invite the traveller guest to rest and drink and talk.

Such themes are also present in the later literature of the Islamic world. The fourteenth century Moroccan traveller Ibn Battuta visited the Tihāma coastal strip of Yemen in about 1330, and describes in his Rihla its principle city Zabid, where he admired the well-irrigated banana gardens and also went on the famous Saturday excursions to the date-palm groves Subut al-Nakhl of Wādi al-Husaib during the date harvest of unripe busr and fresh ripe rutab dates: all citizens and foreign visitors went out, with the women riding camel litters, along with musicians and traders to buy and sell the fruit and sweetmeats and enjoy the pleasures of the day’s outing.

Fertility and festivity went hand in hand, as described a century earlier by the gossipy merchant Ibn Mujāwir in the chapter Dhikr al-Nakhl of his Ta’rikh al- Mustabsir, an altogether more racy account of the same festival. He begins by giving an account of the way in which date palms came to grow in the Tihāma – a caravan from the Hijāz, laden with dried dates tamr, reached the coastal area inhabited by Ethiopians: they ate the dates and threw the date-pits on the ground, where they took root and grew into date palms: the locals observed this and planted more, so that the date palms grew more numerous, with 10 varieties of date palm each with three types of fresh dates, red, yellow and green of varying shades. During the date harvest, people came down from the mountains and from as far afield as Abyan and camped in the palm groves for up to 3 months, snacking on savouries and sour pickles, and drinking a fermented potion of dates and wheat, women drinking with men, which led to many marriages and many divorces! The profits from the Wādi al-Husaib sale of dates and date-products amounted in the year 1227 to 110,000 dinārs after tax: the Sultān and the Bait al-Māl community treasury having increased their share under Ayyubid legislation that lightened the tax burden on hard-working farmers and increased the tax-burden on date-palm owners who merely awaited the harvest from year to year. He quotes Qur’ān, sura Qāf L, āya 10, “and tall palm trees with spathes compact”. At the end of the harvest festival, all would proceed on richly caparisoned and decorated camels, tinkling with bells, accompanied by drums and pipes, to a mosque overlooking the sea at Fāzza, where the footprint of Mu’ādh bin Jabal’s she-camel was still to be seen, as imprinted when the emissary to Yemen was returning to the Hijāz after the Prophet’s death. There men and women would go to bathe in the sea, all mixed together, with much drinking and playfulness and dancing, weekly on Mondays and Thursdays only, before returning home all together.

The geographical literature is also rich in references to the products of gardens and orchards, as in the tenth century al-Hamdāni’s Sifat Jazirat al-‘Arab where he describes Wādi Nakhla planted with banana, sugar cane, henna and potherbs, and Wādi al-Jannat well-watered and planted with grape-vines, safflower, and in its upper reaches the plantings are mixed with all types of fruit trees, and in its lower reaches mixed with bananas, sugar cane, citrons, sorghum, various cucumbers and coriander.

In the late eighteenth century, Sayyid ‘Abd al-Latif Shushtari, a Persian scholar, travelled to Lucknow in India to re-join the great mathematician and translator of Newton, Sayyid Tafazzul Husain Khān. He proceeded from Agra via the once flourishing Islamic provincial capital of Jaunpur: here he found extensive flower gardens and plantations which provided a variety of flowers for the manufacture of perfumed oils by the method of enfleurage: flowers were mixed fresh every day with sesame seeds which after 40 days were milled to produce a highly perfumed oil, which was exported all over India; he also found the extreme heat of the summer cooled and perfumed in garden rooms where vetiver tatties or khuss curtains of perfumed roots were hung at every window and sprinkled with water by water-carriers or even automatically by special hose-pipes, so that the breeze passing through these curtains would be both cooled and scented. Several thousand workers were busy with ice-making for the preparation of summer cold drinks – supplies were guaranteed to all courtiers and citizens in the state of Āwadh. Once he reached the Nawwāb’s capital at Lucknow, he found Chinese and European gardeners at work in the gardens of the 400 royal palaces and villas; not only were they designing parterres, but also introducing new plants, such as the repeat-flowering Rosa Bengalensis, introduced from China, and new techniques, such as the oriental technique of bonsai to make miniature fruiting trees. On the way, he passed under wide-spreading Ficus Bengalensis, which could shelter and cover many travellers, recalling the famous Hadith of the wide-spreading paradise-tree in Bukhāri’s Sahih (chapter 81, section 51, number 6).

Shushtari’s account in his Kitāb Tuhfat al-‘Ālam recalls the earlier account, almost a thousand years earlier, of al-Maqdisi who, in his Ahsan al-taqāsim fi Ma’rifat al- Aqālim, describes the flower gardens of Fārs perfumed with roses and jasmines, and the export of floral scents, oils of violet, water-lily, narcissus, palm-flower, lily, iris, myrtle, marjoram, cucumber, bitter orange. The importance of perfumes was a constant in Islamic culture, following accounts of the exemplary behaviour of the Prophet.

The aesthetic of the Islamic garden was based on a variety of factors: on the climate – hot and arid and therefore needing the contrast of protective shade and the cooling freshness of running water; on the techniques of agriculture and irrigation, developed initially for food production; on the social traditions and needs of the owners and users, from town-dwellers with courtyard gardens within their houses, to rural landowners with more extensive date palm groves in the oases, to noble and royal patrons of large hunting parks; the cultural norms of Islām and the symbolic associations of the literary traditions that had grown out of the study, memorisation and internalisation of the Holy Qur’ān. It was characterised by the following: the shade of densely-planted trees; running water with springs and watercourses; views over the countryside or out to the mountains; privacy within the garden, which is enclosed by walls; the perfumes of roses, jasmine, orange blossom, stocks, queen of the night rāt-ki rāni, pandanus odoratissimus kādhi or keora; birdsong of nightingales or canaries. These gardens were also used for family picnics or as a setting for discreet courtship, but also for more formal receptions of guests; also as a place of quiet conversation and meditation for scholars and mystics and at night for the contemplation of the infinite wonders of the starry sky; most important was their use as economically productive orchards and herb-gardens.

The gardens were also occasionally, subsequent to their use as productive pleasure gardens, used as tomb-gardens, which echo and anticipate the promise of the eternal paradise garden, down to the floral sculpture on the inner face of tombstones. This funerary use of gardens may well have been due to the fragility of ownership of secular land-holdings, and the relative security of funerary or religious property endowed as mortmain waqf. The Prophet himself was buried in his house in Yathrib / Medina next to the mosque of palm trunks in his courtyard, incorporated now in vast and ever-growing modern structures, but still venerated as the Rauda, the garden. In the later tomb gardens, of seventeenth century Islamic India, such as the Tāj Mahal, the Qur’ānic evocation of bliss promised to the faithful comes closest to actual realisations of real gardens – with the caveat that khulud, long-lastingness and permanence, is not a normal quality of earthly gardens, which need constant love and attention and hard work to maintain their order and beauty: even God Himself is always, every day, working to maintain and renew His garden of creation, Sura al-Rahmān LV, āya 29:

“kullu yaumin huwa fi sha’n”

“Every day He is upon some labour”.