The Aesthetic of Promise

The Venice Biennale is regarded as one of the most prestigious cultural events in the international calendar. Its history dates back to 1895; since 1998, it has sought to place new work in a relationship with the past and promote a stronger dialogue with the viewer. The Biennale has expanded exponentially to eighty eight national pavilions, shifting its historic North American and Eurocentric axis to embrace an infinitely wider cultural and political agenda. It is no surprise that the Holy See participates for the first time in the 55th International Art Exhibition (1 June – 24 November 2013) with a pavilion of works inspired by the first eleven chapters of Genesis. There are ten new countries this year, each paying before costs, a fee of 20,000 euros plus tax for the privilege: Angola, the Bahamas, the Kingdom of Bahrain, the Ivory Coast, Kosovo, Kuwait, the Maldives, Paraguay and the remote Polynesian island nation of Tuvalu with a population of 9,847. Like Venice, Tuvalu faces the threat of rising sea levels. It is banking on art to get some action on climate change after science and politics have failed. The Venice Biennale has become a fast moving turntable, a carousel of conflicting geo-political agendas which only the strongest artist and curator can ride with impunity. Sifting out the art from state propaganda and the dead hand of the largely US driven art market is the litmus test of disinterested critical judgement. It is a challenge few critics meet.

It is even more difficult to review the Pavilions of newer entrants to the Biennale who need to make their mark in Venice and satisfy expectations at home. The historical and cultural context for the Middle East, Asia and Africa are daunting - certainly for the woefully uninformed western art critic. But when addressing artists working in the glare of extreme political and social events, the art itself can be so shadowed or compromised by its context that the notion of ‘relational aesthetics’ is tested to its limits. Critical judgments may have to be tempered by consideration of cultural difference, conditions of production, availability of resources, and the degree of the artist’s exposure to an international art world. But ultimately the art speaks or it does not. When the work triumphs it can cross conceptual and cultural borders and achieve iconic status. A good example is The Throne of Weapons, a chair made of cannibalised AK47s from arms dealers the world over by the Mozambique artist Cristovao Estevo Canhavato, known as Kester. It has not only been signed by the artist but also termites who regularly damage African wooden sculptures. Bought by the British Museum in 2005/6, it accumulated meaning and veneration throughout the UK and Ireland. It is regarded as one of the most ‘eloquent objects’ in the British Museum; and was featured in ‘A History of the World in 100 Objects’, the ground-breaking British Museum/BBC radio programme broadcast in 2010. Few works translate so readily. The means of presentation, site and positioning are crucial and for both artist and curator Venice is a cruel mistress.

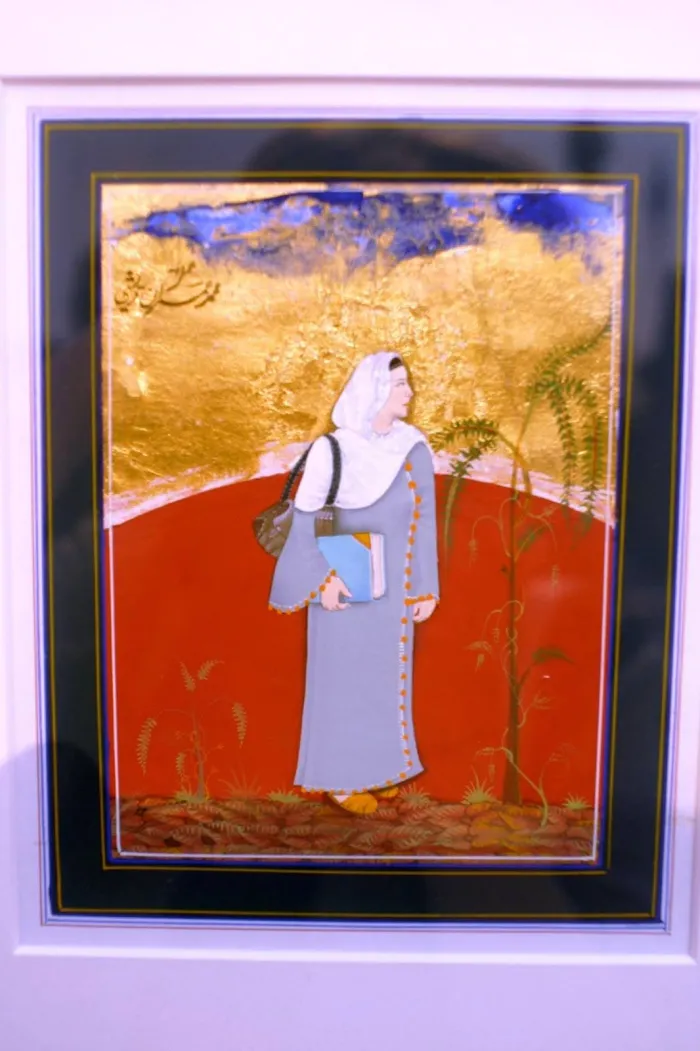

In the congested and overwhelming main Biennale exhibition, The Encyclopaedic Palace, it is possible to entirely miss the series of exquisite miniature paintings by Pakistan artist Imran Qureshi, Deutsche Bank’s Artist of the Year 2013. Moderate Enlightenment 2006-9, harnesses the style of Mughal courtly painting to present the paradoxes of traditional Islamic life and the daily pursuits of contemporary Pakistani men and women, a subtle challenge to western perceptions. The Pavilions of Kuwait and Iraq both aim to puncture preconceptions and to engage the viewer in a dialogue on nationhood and values, but their sites and their curatorial approaches make for very different experiences

Kuwait has waited thirty years to participate in the Biennale. It has a Pavilion north of the Rialto Bridge, a fair walk. National Works presents the national sculptor Sami Mohammad and the internationally exhibited photographer Tarek Al-Ghoussein, son of a former Kuwaiti Ambassador to the UN, who lives and works in Abu Dhabi. The curator is Ala Younis, an artist based in Amman. The Pavilion is an unfurnished marble palazzo, the installation spare and minimal. The exhibition guide claims that National Works ‘disassembles symbols of past glorious times in attempt to re-interpret Kuwait’s modernisation project’. The curator’s essay reverentially and diligently explains the conditions of production, of commission from ruler to subject, ‘of national works by the state for the people and the people for the state’. Artists, especially sculptors, were harnessed to the wheel of urban reconstruction. Sami Mohammad’s gigantic honorary statues of the 11th and 12th Emirs of Kuwait are exceptions; they were commissioned by a private newspaper, Al-Rai Al-Aam, and are not typical of his work. They are apparently not well known in Kuwait and could not be shown in a public space because of ‘the general public’s dissatisfaction with figurative art and their association of them with idolatry’. The statues were cast in London. Their story is told in the Pavilion by a bronze bust presented on a plinth and photographs. The statues’ hieratic woodenness is a telling contrast to the artist’s signature impassioned and bound screaming figures of struggle and suffering which are not shown. Sami Mohammad tells the story of how during the Iraq invasion he escaped the fate of a celebrated sculptor forced to make a statue of Saddam: ‘if I were caught I’d refuse to make the sculpture and the soldiers would execute me and if I’d agreed to do it, the Kuwaitis would’. What is most interesting about the Kuwait pavilion is not so much the work, but the back story of Kuwait’s independence, oil, war, and of the Free Atelier founded in 1959 to train artists for change. The school hosted Andy Warhol in 1977. In the Palazzo’s chilly spaces even Tarek Al-Ghoussein’s fine photographs of bleak urban landscapes look dull and generic.

In contrast, the Iraqi Pavilion takes us to a different space. I had a compelling reason to see it. In 1981, the Iraqi Cultural Centre, then in Tottenham Court Road, London, held an exhibition of drawings, prints and photography: Iraq: The Human Story which I was asked to review. I declined: the exhibition was nationalist propaganda, a justification for the invasion of Iran and a glorification of Saddam Hussein whose achievements and life story were published in a pamphlet to accompany the exhibition. Military images and drawings also illustrated the catalogue text by the Centre’s Director who described Saddam as ‘the symbol of bravery and prudence, standing for the eternal Mesopotamian, one hand holding the sword, the other, the pen’. Thirty years on, the Centre hosted a lecture by Sir Terence Clark, British Ambassador to Iraq from 1985 to1989, during the run up to the Gulf Wars. Clark was of the signatories to the letter from 52 former senior British diplomats to The Guardian (27 April 2004) condemning the US/British conduct of the war in Iraq. He charmed the audience with his fluency in Iraqi dialect, his archaeological knowledge, illustrated with photographs of Iraqi heritage sites by Gertrude Bell, or Miss Bell as she was fondly known in Iraq. He spoke of a religiously tolerant society where even ancient sects, neither Christian nor Muslim, lived undisturbed.

A vision of a revived, healed and an eternal Iraq, a country with nine thousand years of cultural history and accomplishment, is at the heart of Iraq’s National Pavilion. Against all odds, the Iraqi project Welcome to Iraq succeeds where others fail. The Pavilion is supported by the Kurdistan Regional Government of Iraq and the Minister of Culture, Baghdad, corporate and private sponsors and is commissioned by the Ruya Foundation for Contemporary Culture in Iraq, which aims ‘to build a platform that will enable Iraqis in the arts, the young in particular, to benefit from, and participate in international events’. The Foundation was set up by Reem Shather-Kubba and Tamara Chalabi, daughter of Ahmed Chalabi, historian and author of The Shi’is of Jabal ‘Amil and the New Lebanon. They admit the project was ‘a logistical nightmare’. It made good press, The Sunday Times magazine covered the curator Jonathan Watkins, Director of the Ikon Gallery, Birmingham, as he toured Iraq from Basra to Kurdistan under armed guard to meet and select artists, returning at night to the fortified Chalabi family compound in Baghdad. The choice of a curator from a former occupying country is unsurprising; British curators and artists have a long intellectual engagement with the Middle East as ‘official war artists’. Artist and celebrated filmmaker Steve McQueen worked in Iraq and installation artist David Cotterrell made solo journeys to Afghanistan in 2007. Both are represented in the Imperial War Museum, London. Jonathan Watkins also had form as a broad based international curator with strong interests and experience in the Middle East, and has curated Biennials worldwide, including in Palestine and Sharjah.

Watkins decision to move away from art of the diaspora to try to work with artists living in Iraq was a departure from the Middle East presence at the last 54th Venice Biennale when the main focus was on established international artists. The inaugural Iraqi Pavilion had six émigré Iraqi artists and the major pan Arab exhibition, The Future of a Promise, showed works by twenty two artists including the two well-travelled and exhibited Iraqi artists, Janane-Al-Ani and Ahmed Alsoudani. As Hassan Janabi, Iraq Ambassador to UN agencies in Rome, noted: ‘getting Iraqi artists who live in Iraq is not an easy job….it could be tedious and possibly create tension... Instead, they sought out artists living in the outside who could truly reflect what constitutes an Iraqi artist’.

In challenging that view, Watkins took the risk that in a war depleted country he would not find work which could hold its own at an international stage. His mission would have failed had he sought to make a conventional exhibition. Some of the work is undeniably weak and would pass unnoticed in an art school degree show. But by conceiving the Pavilion as an act of hospitality he brings about a powerful connection between the artist and the viewer , the host and the guest, which is rare. Watkin’s curatorial strategy is not new. It takes its premise from the 2012 Liverpool Biennial and the accompanying book The Unexpected Guest which is an anthology of texts addressing hospitality from perspectives of colonial history, spatial politics, citizenship and the exercise of power. The question is: does the work overall stand up to that of the nomadic internationalist artists of the Venice Biennale whose art is hawked around the world, has high ‘production values’ and speaks the language of resources and money? How does it fare alongside the craftily polished sculpture and paintings of the British celebrity artist Mark Quinn? Quinn’s inflatable replica of his nude marble sculpture of Alison Lapper, an English artist who was born without arms, which once sat defiant on the plinth in Trafalgar Square, now queens it over Venice, like one of the gross cruise liners that dwarf the Venetian skyline. Watkins answers this by declaring that ‘we are not so hung up on art and similarly value found objects and artefacts. The Iraq Pavilion itself is an extraordinary found object’. Moreover, ‘the exhibited work is inextricably bound up with this context’.

He shows works by eleven artists of two generations: cartoons, paintings, sculpture and installation in lofty first floor rooms with light flooding from the tall windows of Ca’Dandolo, a Venetian palazzetto overlooking the Grand Canal and conveniently facing the San Toma vaporetto stop. Such an accessible and prominent site attracts locals, tourists as well as professional Biennale visitors. They are enveloped by the gentle ambience of the Iraq Pavilion where they can sit in comfort among fine Kurdistan carpets and rugs, watch laptop short films, listen to the haunting music of the Oud, drink tea in the customary delicate glass and eat sweet kleytcha biscuits warm from the kitchen. Everywhere there are neat piles of well chosen books on Iraq from the Iraq National Library and Archive, enough for weeks of browsing. Works of history, literature and politics sit alongside children’s’ books: Babylon’s Ark: the Incredible Wartime Rescue of the Baghdad Zoo, The Iraqi Cookbook and Shoot an Iraqi: Art, Life and Resistance Under the Gun. The latter could be the by-line for Welcome to Iraq. It is a place of respite from the circus of the Giardini, the main Biennale site where queues blocked the entrances of the habitually self-important US, German and French Pavilions which have swopped sites in a trite gesture of inverted nationhood.

At the Iraq Pavilion the guest enters another world. I was hosted by two of the artists who work together in Basra as WAMI, Yareen Wami and Hashim Taeeh. They talked about the conditions of the Iraqis and of their own artistic isolation, the lack of resources, galleries or any art infrastructure: ‘nothing has changed for us’. Over 5000 works of art, looted in 2003 from the National Museum of Modern Art in Baghdad, are missing or destroyed. WAMI make finely crafted sculpture and furniture from cardboard. Every ridge and corrugated furrow counts. The faux minimalist aesthetic of Muji, the Japanese retail store, is used to coruscating effect in an eerily monastic bedroom installation that speaks volumes about confinement, making do and getting by, on nothing. Cardboard, as cheap ubiquitous material, is common currency in the British art room, but it is rarely recycled with the simplicity, subtlety and wit of WAMI’s figure and portrait reliefs which quote their Sumerian heritage and nod to Western modernist influences from Klee to Braque.

The work of Bassim Al-Shaker, a painter living in Bagdad, evokes an earlier landscape art, the naturalistic realism of the nineteenth century French artist Jean- Francois Millet. Al-Shaker fluently paints the vast water lands of the southern Marsh Arabs who were displaced when the marshes were drained and degraded by Saddam Hussain and are now being slowly restored. Paintings of date sellers, reed harvesting, herding and milking hang in place of the marine paintings which usually grace the walls of the Ca’Dandolo. Shaker’s works may look romantic, bucolic and are hardly contemporary, but like Millet’s great Angelus of 1857, these are paintings of both mourning and celebration, full of meaning for contemporary Iraqis. The more overtly political works of conflict by

Jamal Penjweny, who was trained at the London Institute of Photography, are known and have been published internationally. He now lives in his birthplace in Kurdistan, Sulamaniya, where he runs an art café. His photographic series Saddam is Here of ordinary Iraqis holding an image of Saddam in front of their faces are both memorial and curse. As the artist says: ‘they cheered for him, they beautified his cruelty… Saddam is here’. This is the closest any of the works come to commentary on sectarian divisions. Penjweny’s film Another Life made a powerful impression on everyone I spoke with. It is a roughly edited day in the life narrative of the fate of mostly young Muslim men forced through poverty to smuggle crates of alcohol from Iraq into Iran. One holds up bottles of Scottish liquor, another shot has the label ‘Danzil Vodka Made to Chill’. The boys are angry, some laugh, desperate in the knowledge that on every mule run they face murder by the customs officers they have not paid off. They die. We are left feeling anger with their paymasters, with the hypocrisy and the venality of those in power.

The Iraq pavilion shows the plight and the resilience of artists living now in Iraq where roiling bloodshed has killed hundreds of thousands. It is of course incongruous that their works furnish the theatre of a Venetian palazzo on the Grand Canal, but they represent actors in a much larger drama: where the sweep of history is before us and Baghdad, Arab City of Culture 2013, becomes again Dar-es-Salaam – City of Peace. The Iraq Pavilion stands for the promise of a civil society where artists and art have a place and value.

The catalogue is written simply, no theorising or art speak, for a general public. There is a question and answer interview with a soldier in the Iraq Special Forces:

‘What is your favourite place?’

‘Kurdistan’.

‘Describe Iraq in one word’

‘Precious’.

‘What do you love most about Iraq?’

‘Affinity’

‘What do you hate most about Iraq?’

‘Violence’

‘Where is Venice?’

‘Spain’.