Dhaka

Every city moves to its own beat. Although I am a city dweller through and through, it took me some days into my visit to Dhaka before I could sense its unique rhythm. It was only when my friend Mahmudul Hasan took me one evening through the narrow streets of the Old City, down to the Buriganga River boat terminal at Sadarghat, that I felt the Dhakan bassline in my belly for the first time.

As our rickshaw approached the Buriganga that defines the southern edge of the city, the full moon lit up a portside vista – a rank of passenger ferries waiting to cast off, boarded by the streams of people making their way down the gangplanks carrying bundles of possessions and goods to sell, families, many with small children, and elderly people in tow. The low long boom of the ferry horns cut across the incessant treble ‘beep, beep, beep’ of cars and auto-rickshaws trying to gain an inch advantage through the traffic-jam streets.

Men with nothing else to do leant silently against the riverside wall, smoking cigarettes and watching the flow and ebb. A stall with heaps of toothbrushes was doing good business, making money a few Bangladesh Taka at a time selling to those who had forgotten to pack the essential item for an overnight trip. On a warehouse overlooking the wharf hung a huge banner by the ruling Awami Party, with a picture of its leader Sheikh Hasina’s hand raised as if imperiously waving off the masses. The slogan read: ‘The Principal of Sheikh Hasina is the Development of Democracy’.

The Sadarghat ferry terminal is one of the largest in the world, with around 200 passenger vessels carrying 30,000 people in and out of the city every day. Mahmudul explains that there are four classes of tickets, the cheapest will buy you a bit of floor down below, while the well-off squat above, coddled in their own cabins and luxurious saloons with TVs and attendants on hand. The ferries are a cheap way for the poor migrant workers who hail from the southern divisions (provinces) of Khulna and Barisal to get home and back. If the Buriganga River is the aorta of the city, channelling the rural poor into the heart of Dhaka, then Sadarghat terminal is the valve that regulates its beat.

Significant human settlement in what is now Dhaka probably goes back to the Mauryan Empire (324-185 BC) founded by Chandragupta Maurya and expanded by his son Bindusara and grandson Ashoka. There is evidence that Bikrampur (‘City of Courage’), originally located in what is now the Munshiganj neighbourhood of Dhaka, was a regional capital during the Sen dynasty, founded in 1097 AD. The first Mughal Subahdar of Bengal, Islam Khan Chisti (1570-1613), subjugated the province and established Dhaka as its fortified capital in 1608. He named it Jahangir Nagar (the City of Jahangir) in praise of his emperor. Under the Mughals, for the next 140 or so years, the Queen of the Cities of the East expanded and its trade and industry boomed. It was the centre of the world’s muslin and cotton industry, employing an estimated 80,000 skilled weavers and turning it into a cosmopolitan world city. And then after the Battle of Plassey in 1757 the British East India Company took control, ushering in a brutal chapter in the life of the city and its inhabitants.

That vision thing

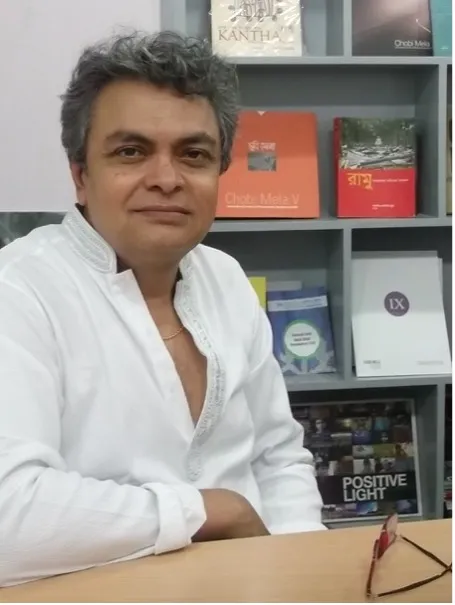

On the first morning of my visit I sit in the Dhaka headquarters of Drik, the world-famous photographic agency founded in 1989 by Shahidul Alam, a tireless and fearless social activist. He set up Drik to wrest back ownership of the image from the Western gaze and to empower photographers from what he calls ‘the majority world’. Every two years Drik (Sanskrit for ‘vision’) mounts Chobi Mela, an international festival of photography, the biggest of its kind in Asia. Shahidul also established Pathshala, the South Asian Institute of Photography, to tutor the next generation of homegrown socially conscious photo and film journalists. He set up the Bangladesh Human Rights Network (banglarights.net): ‘an independent platform for media professionals and activists… to champion principles of democracy, give voice to people at grassroots levels and address social inequalities and domination at national and international levels’.

Shahidul rarely stands still. The week before my visit to Dhaka I bumped into him on a Tube escalator in central London, and just as I arrived in his city he was jetting off somewhere else. But I am graciously hosted at Drik’s headquarters by its CEO Saiful Islam. After sketching the history of Drik, Saiful moves on to a recent multi-faceted project that is clearly dear to his heart – re-establishing the importance of muslin in Bangladeshi culture. This is a delicate cotton fabric described as ‘woven air’, produced from a strain of the cotton plant that once grew in abundance along the banks of the Meghna and Brahmaputra Rivers.

Saiful explains to me that ‘our heritage has been usurped by others. The only book on muslin prior to our project was by the Victoria and Albert Museum, but it hardly mentions it as a product from a plant that grew along our river banks. It was manufactured here, from here it went global. It travelled all the way to Ancient Rome – the Romans had to put in an order three years in advance, it was in demand in Indonesia, where they had to wait two-and-a-half years. We had traders from twenty nationalities based here in Dhaka in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, Afghans, Turks, Italians, the Dutch.’

What put an end to the Bangladeshi muslin trade? The British East India Company of course. ‘As the East India Company got in on the act and looted India, they destroyed the muslin industry,’ says Saiful. By 1800, restrictions on trade, taxation and astronomical tariffs designed to protect the Lancashire cotton industry had cut trade in the city by a full half in the space of 40 years. Destitution, followed by a famine (1769-73) cruelly presided over by the British, emptied the city and wiped out half the population of wider Bengal. In recent years, there has been a revival in a particular type of traditional and uniquely patterned fine muslin known as Jamdani, or by its original name Dhakai, but the cloth is still virtually unknown in its purest hand-woven form. Saiful shows me a photo of a nineteenth century piece of the finest muslin in his possession, purchased at a price he would not disclose to me from a private collector.

For Saiful, muslin is ‘a question of identity. We are identified as a nation that produces ready-made garments and for the terrible factory fires that kill hundreds of workers, but we do have a richer heritage. We want to offer the nation another identity that we can be proud of.’ I am suddenly aware that in preparation for my trip to Dhaka I had picked up some T-shirts in my local Primark for £3 each: ‘Made in Bangladesh’. Another major aim of Saiful’s project, very much in the Drik ethos, has been to elevate the contribution of those ‘nameless and faceless’ weavers whose undervalued skills have been handed down through generations. ‘I want to talk of the land and the people from where muslin has sprung and how this glory was achieved.’ He wants to give power back to the small producers. On my arrival at Drik’s HQ I had briefly met Al Amin, one of the master weavers involved in the project. In the literature accompanying the Muslin exhibition, Al Amin has his say:

We have worked to revive the muslin that we have heard of from our ancestors. I am not literate. I have heard from my ancestors that muslin was so fine and thin it could be kept inside a matchbox. We have never seen it. We have now proven that we are able to revive our age-old tradition. But the task was not easy! We need a certain cool temperature to do this. Mostly at dawn and after sunset.

The project is ongoing, with Saiful now working with plant geneticists on samples from botanical institutions such as Kew Gardens to trace the evolution of various strains of the muslin cotton plant and see if he can track them back to Bengal.

He also talks to me about early plans Drik has to work with imams and mosques, perhaps mounting exhibitions for prayer-goers to look at. ‘Our point is, there is no need to alienate these guys – there is a danger in that. My dream would be a mosque that every week has exhibitions, activities and discussions. But to do that you have to be trusted and accepted. To me part of the identity of this country is Muslim, not secular, but it is not monochrome. My mother prays five times a day and is also at the head of one of the largest women’s organisations, dealing in legal affairs. There is no contradiction.’

Then, like many of the conversations I have in Dhaka, Saiful moves on to the political evolution of the country and the present situation. I ask Saiful to describe to me the psyche of present-day Bangladesh. He points out the small flag hanging on the wall behind me. A yellow map of Bangladesh nestles inside a red circle against a black background. He explains that it is handwoven, and was originally tied to the barrel of a freedom fighter’s rifle during the 1971 War of Liberation. The map of Bangladesh was later dropped, leaving the red circle against a green background. ‘We had a separation from Pakistan and a very violent war,’ he begins. ‘We have normally been quick to rebel against external authority. I don’t think we much believe in the Ghandian ideal of non-violence, which in my opinion just allowed the British to stay longer. We had Sarat Chandra Bose, a brilliant charismatic leader.’

But then he pulls back to explain what he sees as the root of the country’s historic identity: ‘Bangladesh means “the country of Bangla”.’ As Saiful puts it, the country is small (equivalent to half the size of Texas) but the language is big, reckoned to be the seventh or eighth most used language globally, with 210 million speakers. It was student-led resistance against the Pakistan government’s attempt in the early 1960s to downgrade the Bengali language and ban Bengali literature and culture, including the works of Tagore, from schools and colleges that fed into the desire for independence.

Next is Bangladesh’s pan-Indian cultural identity: ‘A lot of our rituals and culture has a Bangla-Indian flavour. So the way we celebrate our weddings is not “strictly Muslim”. I don’t think we even care or understand what “strictly Muslim” is. We have a rich cultural heritage of song, of Tagore, of festivals.’ Then there is the rural life of Bangladesh and its elemental relationship with water, particularly the country’s rivers. Bangladesh has the highest population density in the world, with two thirds of its people living in the rural areas. The land itself is a product of its 700 rivers and the fertile silt-rich soil that lies in between them. It was anger at the Pakistani authorities’ lacklustre response to the devastation and deaths that a terrifying cyclone wrought in November 1970 that finally tipped Bangladeshis into insurrection.

Our conversation returns to 1971 and the political forces that emerged from that period – the parties, big business and military interests and how the ongoing significant economic, social and political interventions of non-governmental organisations (NGOs) and donor organisations has sought to influence the direction of the country’s development. And then there are the regional politics and geo-politics, including Bangladesh’s relations with India, China, and US foreign policy.

What of the country’s psyche? ‘It is young at heart, because it is not fully formed.’ Bangladesh has a young demographic who only know of the war through the interpretation of politicians and historians. Saiful tells me that nearly half of the population is under 25 years old, ‘desperately trying to establish themselves, getting a degree and the hope of a job’.

Bangladeshi politics revolves around the struggle over the interpretation of the 1971War of Independence. Also known as ‘liberation war’, it has a vice-like mythic hold on the politics and people of the country. The Awami League today lays claim to its inheritance through the dynastic figure of prime minister Sheikh Hasina, whose socialist-leaning father Sheikh Mujibur Rahman is regarded as the nation’s founding figure. Saiful tells me that the Awami League has driven its identification with 1971 to such a point that the party, not the people, have come to be seen (at least in the League and its supporters’ eyes) as the historic agent of the country’s liberation. ‘It was a people-led movement, dominated by a party at whose helm was a unique individual – no doubt – but today it’s as if the party brought the victory about,’ – similar, in a way, to the African National Congress’s present claims for its role in ending apartheid in South Africa.

The Awami League has used its 1971 hegemony to pound and crush its political opposition. The Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP) has been labelled extremist sympathisers, mainly through its past electoral alliances with the religious party Jamaat-e-Islami, whose leaders militarily sided with Pakistan during the War of Liberation and formed death squads to carry out mass executions of pro-independence activists and intellectuals.

While I am in town, the Dhaka Tribune reports a rally speech by Sheikh Hasina in which she promises further economic development: ‘Insha Allah we’ll do that…in the spirit of the Liberation War…If necessary, I’ll sacrifice my life like my father to free this country from poverty,’ before reportedly coming down hard on BNP, saying ‘whenever BNP comes to power they give rise to militancy, carry out killings and indulge in corruption and looting’.

Many people I talked to during my visit to Dhaka, whatever their political allegiances, were clearly worried by the way in which the increasing domination of one party has acted to erode democracy and the essential element that keeps it alive – dissent. For Drik this politically engendered silence has struck very close to home. In 2010, Shahidul Alam’s visual exhibition ‘Crossfire’, (the term used by the government’s notorious Rapid Action Battalion to explain away extrajudicial killings of those they deem troublemakers, terrorists or ‘criminal elements’), was shut down by the Dhaka police. It was only reopened after Drik’s lawyers went to court. Saiful feels that what has been a traditionally vibrant, participatory political culture is becoming ‘uniquely dissent-less’. He detects an increasingly general reluctance to speak out, whether it be against widespread corruption, the hundreds of ‘disappearances’ of opposition activists, Islamists, as well as environmental issues such as the hot-button topic of the building of an India-backed coal-fired power plant in the protected forests of the Sunderbans, the treatment of workers and the poor, or the neo-liberal economics feverishly pursued by successive governments. Those in power have relied on year-on-year economic growth and praise from the World Bank on poverty reduction measures to bolster their base, attract foreign investment and reap the rewards. The political class is intrinsically knitted into the business class, with the armed forces increasingly allowed to move into the economic sphere (presumably as a way of keeping them onside).

Saiful says the triumph of quantitative measures of growth over qualitative measures of the health of civil society has come at a cost. ‘The material growth is there, but we need to have a far bigger say in terms of what alternatives we can pursue. There is a lot of activism on the social and cultural side, but not enough on the political. Even on the youth side, politics has become how to profit from the system.’

But Saiful is not at all pessimistic. ‘In the future, we want Drik’s work to be more strategic. To bring topics to the table to people who would normally shy away. We will continue to highlight stories that matter. At the beginning of every journey, there is an individual, and at end there is a story, and beyond that there is an idea. That is what we do.’

The city and the slums

Dhaka is one of the world’s most densely populated cities, growing by four per cent a year. No-one knows the actual number of people living in this ‘megacity’, but it is somewhere around 17 million. It continues to pull in migrants from the rural areas in the south, where poverty is at is severest. A 2014 census estimated that there were 1.6 million people living in slums in the Dhaka division, reflecting an increase across the country of 60 per cent over the last seventeen years.

I visited the studio of architect Nazmus Saquib Chowdhury, located in the Mohammadpur region of the city. For many years, he has been researching and advocating the needs of the built environment in urban slum areas and those in rural areas affected by cyclones, floods and soil erosion. The basic principle of his work is that ‘every person has the right to live and work in a physical environment that takes care of their dignity, privacy, health, comfort and well-being, light and clean air; the elements that nature provides being an integral part of it’. While studying in London he became the founding director of PARAA, a social enterprise formed to push forward this agenda.

Nazmus’s argument is that the built environment has been largely been neglected by NGOs. ‘I got to realise that this particular side of development was being left out. The people I met in NGOs were mostly from a social science background. They were focusing on the environment and disaster management, not on the technical or infrastructural perspective. The areas they work in are absolutely essential to save lives, but in terms of long-term rehabilitation, the funding is less and so the work in that area is minimal.’

When he came back in 2012 from studying for his MA at London Metropolitan University, Nazmus realised that there were scarce funds for the work he saw that was needed, and so he sought out consultancy work where, in his words, ‘there was some glimpse of a built environment’. He describes how at an urban level the government is concentrating on mass infrastructure projects – the big picture if you like – but the detail, for people who live in the slums for example, is largely missing. Nazmus becomes animated when he talks about the ‘problem’ of Dhaka’s slums. ‘How many generations are there going to be living in the slum areas if we cannot address these issues?’

‘When you think about slum areas, you think of a population living in a place that does not belong to them. A place where the poorest of the poor live, who do not have any kind of fixed assets.’ But for Nazmus a slum is neither essentially about ownership nor possessions – it is rather ‘a condition where people are living without the chance of a better environment with light, air, ventilation and sanitation’. For Nazmus, this is not a ‘problem’ for slum-dwellers that the rest of us can afford to turn away from – it impacts on wider society and the wider environment.

The solution can only be a holistic one, he says. He takes the example of sanitation to illustrate this:

‘When there are health issues such as diarrhoea and malaria, the NGOs tell us that the solution is to provide safe drinking water. So they explore the cheapest way of filtering the water. But will the cause of malaria be gone? I don’t think so – it arises from a lack of sanitation or drainage during the rains, or the non-disposal of garbage.’ In other words it is the symptoms, not the root cause, that are the focus. ‘But if you don’t tackle the causes, the problem will persist. You can find funds for clean drinking water, but you might not be able to get funding to change the whole water system.’ To back Nazmus up, the 2014 census report found that four out of ten slum dwellers use what are termed ‘unhygienic toilets’.

The figures also showed that the vast majority of them find a living in the service industries, including garment manufacture, general trading (for example street vending and shop work), rickshaw-pulling, and domestic service. Nazmus argues that ‘the authorities must realise that there are needs for this group of people – they serve the city. They need to be officially legitimised’. The slum dwellers have a precarious existence without legal rights, yet many live on government-owned land, and pay ‘rent’ to unofficial landlords, including corrupt local officials. (The census says 65 per cent of them pay rent, with only seven per cent living ‘rent-free’). They go to work in the city, and their children go to school.

These communities have invented ingenious ways in which to protect themselves. Nazmus discovered that ‘they have a unique way of dealing with fire, thieves and attacks (with arson becoming more frequent as thugs, hired by powerful interests, try and force slum dwellers off)’. He continues:

They have a series of whistles in each house and the tone of the whistle alerts people as to whether they are being threatened with fire, or someone is going into houses stealing. When I went into a particular slum area for the first time, my presence immediately went out to some big guys that there is a stranger around. It was not until later that I got to know about it. One guy told me, ‘We knew when you were here and we were observing you. This is our secret security mechanism.’ I took it as very positive; that they were protecting their homes.

Nazmus believes that rather than denigrating slum dwellers, their contribution to the city should be recognised, their existence validated and their children given a chance to realise their potential. Five years ago, he conducted a feasibility study for a community learning centre at the nearby Mohammadpur Geneva Camp, where a community of Biharis live in poverty and degradation. The report was titled ‘Unlimited Dreams in Limited Spaces’ and started with this case study:

Junayed, a fifteen-year-old boy and a student of class 9 dreams of becoming a chartered accountant one day. Living and studying in the dark and filthy 8.69m2 room with stained walls does inhibit such a dream. He knows that he will have to be well established in his life to take care of his aged parents and his only younger brother who suffers from serious head injuries. Ignoring the buzzing sounds coming from the camp street and the loud noise from the neighbour’s television, he sits in the dark room, trying his best to study. He wishes to be in a place devoid of bad odours, loud noise and poor lighting, a place where he will be able to concentrate on his studies so his dream can come true.

I ask Nazmus whether the political classes and policymakers are sympathetic to what he wants to achieve. This is what his architectural practice should be doing all the time, I say. He tells me he has had some tough arguments. Part of the problem is that NGOs, national and city politicians are all looking for short-term results that they can take credit for. But he is ready any time to lend his vision, insight and skills.

Kushtia: Mystics and Marx

Mahmudul Hasan tells me he has organised a trip out of Dhaka. He and a couple of friends are taking the coach to the town of Kushtia, a hundred miles west of Dhaka and around fifty miles from the border with West Bengal. Just out of the town lies the village of Cheuria, the site of Lalon Akhra, the shrine of Lalon Shah, the nineteenth century Baul mystic and social reformer whose philosophy has had a seminal impact on Bengali thought and culture. He tells me that thousands of people, including the most famous Baul singers and fakirs who follow in Lalon Shah’s footsteps, are now making their way to the shrine complex to take part in the Dol Purnima (Moonlit Night) festival. The four of us will meet at the coach station and travel that afternoon. Even though it is only 100 miles away Mahmudul warns me it will take us maybe eight hours or more to get through the clogged roads. I pack my toothbrush and we are on our way.

At the coach station, we meet up with our travelling companions. Jannati Hossain is a young woman who is building a small business selling traditionally made earthenware that she adapts into household decorative items. Rupom hails from Chittagong and is studying at Drik’s Pathshala institute. We get the cheapest class of ticket and board our coach, windows open to create some air-conditioning. The coach has to fight its way out of Dhaka along the western corridor and eventually the cityscape gives way to countryside. We cross the Bangabandhu Bridge, the eleventh longest bridge in the world that spans to the Jamuna River and then later on pass over another river crossing and into Kushtia. As night falls Rupom turns to me and says, ‘This is the real Bangladesh – everything looks beautiful in the dark.’

We arrive in town around midnight, have a quick meal and then book into our cheap hotel. At 5am I am woken by a mosquito buzzing in my ear and the sound of people breaking into song in the street below my window. Soon we are riding a CNG (auto-rickshaw) along the rain-sodden route, across a railway line and down a village path to the Lalon Shah complex. The festival is already up and running, thronged with festival-goers moving past the stalls towards Lalon Shah’s mausoleum, where devotees are queuing up to honour him. I read a short biography of Lalon Shah set into a plaque:

Lalon Shah – The Humanist (1774-1890)

Lalon Shah was the host of many identities – a mystic devotee of the Baul discipline, a humanist, a social reformer, a philosopher, a composer, lyricist and a great singer.

The text recounts the story of how teenage Lalon, while on pilgrimage, contracted smallpox and was left on a Cheuria riverbank to die. He was found by a local farmer and nursed back to health by his wife. This allowed Lalon Shah to be reborn into anonymity – he deliberately drew a veil over his past and what community he was raised in, allowing him to construct a syncretic egalitarian philosophy unhampered by defined religious affiliation, ethnicity, caste or class.

Mahmudul has someone important he wants me to meet. We make our way into a large compound, where a stage has been erected, upon which are seated leading devotees, fakirs and a band of Baul musicians, attended by a large audience of around 300 people. A morning ceremony is underway – songs, poems and speeches. Mahmudul explains that they are performing a recitation named ‘The Shepherd’s Song’. Then an older man, draped in white, with thinning long white hair and black spectacles takes the microphone. For maybe three quarters of an hour he talks to the crowd, his lecture interspersed with music and chants. I watch him, and although I can’t understand Bengali, I know a political orator when I see one. I ask Mahmudul who he is and what he is saying. ‘This is the man I want you to talk with, his name is Farhad Mazhar, a very important figure on the Left. He’s talking about Lalon Shah and what he stood for.’

After the recitation, I am invited by Roshan Fakir to join him and maybe forty of his followers for breakfast. Roshan Fakir is one of the present-day leading disciples of Lalon Shah, and with his wife leads an ascetic existence in a small settlement in Kushtia. I am seated on his left and he turns to smile at me in welcome. On his other side is Farhad Mazhar, who leans across to talk me through the mealtime ritual. First, everyone seated on the floor in rows gets as earthenware bowl. This is filled with water so we can wash our hands. Then a helper comes around with a pail and empties the water out. Then we get rice, vegetables and sauce put in our bowl. We wait. The guru is given his portion by his wife who prostrates in front of him and gives thanks. When she finishes this short ritual, we are allowed to eat. Mazhar explains that everyone in the community eats, they eat together and at the same time. Thus, no-one goes without.

Afterwards I sit down for a wide-ranging conversation with Mazhar. Now seventy years old, he is what I would describe as a leading member of the ’68 generation of revolutionaries; schooled in Marxism, but of the New (anti-Stalinist) Left. He studied pharmacy at university before being forced out of Bangladesh in 1972 in the aftermath of the violent political fallout from the division between those in the Awami League who believed national liberation to be the end goal, and the leftists who believed it only to be the beginning. As Mazhar put it to me, ‘National liberation was important to support because it was an act of the oppressed. To fight back against oppression, they needed an identity to unite the people. But I don’t give a damn about Bengali nationalism. Nationalism is another form of racism, and nationalism also produces fascism.’ In Mazhar’s view this nationalistic end game is now coming to pass in his country.

He has had an extraordinarily prolific, influential and activist political career. According to filmmaker and author Naeem Mohaiemen, in the 1970s Mazhar was aligned with the Sharbahara Party, that trod the same path as the armed struggle of the Indian Maoist Naxalite movement. He ended up in New York, where he worked as a pharmacist, studied economics and mixed in radical circles. In 1984, he set up a counter-NGO known as UBINIG (Policy Research on Alternatives to Development). Mohaiemen describes UBINIG’s many projects as encompassing ‘environmental activism, alternative to traditional farming methods, opposition to Bangladeshis being used as guinea pigs for abortion pill RU 486, criticising American media focus on child labour as an excuse for UN protectionism’ and the establishment of a feminist bookshop in Dhaka. Mazhur has always been outspoken and sometimes been made to pay the price. In 1995, he was arrested by the BNP-led Bangladesh government and detained without trial under the Special Powers Act after he wrote an article denouncing the bloody suppression of the Ansar Rebellion of soldiers demanding better working conditions. There was a storm of protest inside Bangladesh at his jailing and internationally. Nadine Gordimer, Jacques Derrida and Mahasweta Devi wrote a letter to the New York Times demanding he be released.

So why Lalon Shah? I ask. ‘I want to ground the Left’s thinking in those traditional discourses that have been all but eliminated by modernity,’ Mazhar tells me. ‘Modernity claims that only the Enlightenment counts in civilisational terms, and that we are all uncivilised, have nothing to offer; we cannot create or originate anything. So, I want to identify trends in Bengal that have a global significance and which are based on community building against the centralised modern state which is very repressive, to find ways of avoiding the conflictual model that still exists in my society, and finally, as a Bengali, to critique from my own traditions.’

‘Here today, we are celebrating Lalon Shah. Why? Because he started a political movement that was also a spiritual movement. He didn’t believe in caste or class, and so he started an anti-caste movement. He attempted to persuade through love and not force and through “theatre” [such as the meal ritual]. He also argued for a [human] food system that would also maintain all other life systems.’

Mazhar explains that it has been a long path to Kushtia. ‘I went on this journey where I came to the realisation that Marxism is essentially an extension of the European Enlightenment – which is fine – but I found that what has been developed from the teachings of Marxism is not going to work in a society like Bangladesh. I find it has a serious flaw in denying the role of subjectivity, or the role of the spirit.’ That doesn’t mean that he has abandoned Marxism, or is about to go to New York ‘and start Hare Krishna’ as he put it. Neither will he criminalise people fighting back against ‘this ugly system’ and the ‘war on terror’, including Islamists targeted by the Bangladeshi state for summary execution, even though he doesn’t necessarily agree with what they stand for.

Unlike many on the Left internationally, Mazhar is not an enemy of religion. He opposed the Awami League and Sheikh Mujibur Rahman’s 1972 declaration that the new Bangladesh should be a secular state. ‘It simply meant you want to eliminate Islam from Bengal. I understand that in the West the Enlightenment wanted to break the power of the Christian Church, because it was an oppressive force. But that is particular to Europe. Our thinking, culture and practices are very different.’ He is a celebrated poet, and has recently taken to writing within an Islamic poetic framework because, in his words, ‘progressives, in trying to reject [the reactionary face of religion] have also thrown away its core…In the battle against imperialism, we need to rediscover that which is our own asset, the core of our being.’

‘I go to all the madrasahs where I have good relations,’ he tells me. He adds, ‘many don’t like me, which is fine, no problem. They think I’m not a good Muslim: I don’t follow shariah, I don’t go to prayers very often – but I do fast very well. I tell the muftis that Bangladesh is a brutal state run by killers and robbers – what’s the point of demanding shariah law on the top of a state that is getting more and more fascist?’ He concludes by arguing that the modern centralised nation state is parasitical upon the mass of the population, and runs counter to the development of communities. ‘The Left globally has to redefine revolutionary subjectivity for 2017 – how to organise, how to connect with popular movements that are fighting back.’

It’s been a fascinating but exhausting conversation for both of us. I will meet him again when I am asked to partake in the communal lunch. Mazhar is an extraordinary, intellectually imaginative figure, and I am thankful that I have met and talked with him.

I retreat to the back of a wooden tea shop to hang out with Mahmudul’s student friends from the University of Dhaka where he studies. I talk with a nice middle-aged lady who sat beside me. She tells me that her name is Ayesha Khatun and she is a local primary-school teacher. She earns the equivalent of £350 a year, teaching her class of 80 children. She would like a wage raise – maybe another £100 a year – to help her make ends meet.

We leave the festival site and take a ten-minute walk back through the village streets and down to the bank of the Kaliganga river, which is a tributary of the Ganges. It is a peaceful idyllic scene – kids mucking about on small boats, nets hanging to dry, and locals and Lalon Shah devotees washing themselves and their garments in the river.

We walk back to the festival, where, unfortunately, due to my foreign appearance and height, I am spotted by the local police officer in charge of security. He engages me in polite, formal conversation before nodding towards his numerous underlings who are lounging about bored, weapons on their shoulders and at their hips, marooned amongst the peace-loving crowds. He calls out and one of his shotgun-toting officers appears at my side. The chief tells me that the officer will now be my official police bodyguard for the rest of my time at the festival. I protest feebly that I don’t really need an armed escort, but he’s not having it. For the next few hours the officer shadows me, as I go to the latrines, trawl the stalls and watch a medicine-man convince onlookers that a painkilling ointment made from the venom of small black scorpions (one of which he dangles by its tail) is worth buying, and the efficacy of the fattest leeches I have ever seen. I am now attracting a lot of attention as people wonder who the armed officer is protecting (and why). I retreat to back of the tea-hut where Mahmudul’s student friends gently rib the officer sat next to me, which makes me a little nervous.

And then we suddenly realise we are late and must rush for the coach back to Dhaka. I discharge my protector, we jump on a cart and then into a CNG back to town and onto the coach for the bumpiest, bone-crunching, headache-inducing, traffic-clogged ten-miles-an-hour journey I have ever, ever experienced.

Those who ‘do politics’

The lives of Dhaka’s Bihari population remain perilous, ever since they were rendered stateless at the birth of the state of Bangladesh. Originally migrants who moved into East Pakistan following the partition of India, this Urdu-speaking population were regarded as a fifth column during the War for Independence because of their collaboration with the Pakistani armed forces and anti-liberation paramilitary death squads.

The community were dealt a collective punishment during and after the war, including violent reprisals, arrests, mob attacks, dispossession and mass killings. A Bangladeshi journalist who works in international media told me that this communal dimension of the 1971 war has in his opinion yet to be fully confronted by Bangladeshis in that, in his words, ‘their plight was never documented’. He has been convinced by eyewitness accounts that at least some of the killings were orchestrated by pro-independence forces and ‘the perfect narrative’ of the war of liberation has acted to suppress this bloody episode. Unfortunately, the Biharis have recently been caught up in an unhelpful intervention by some Pakistani commentators and writers whom Bangladeshis accuse of cynically highlighting the atrocities against Biharis as a way of attempting to underplay or cloud the genocidal campaign by the Pakistani forces.

Many of those Biharis who survived ended up in refugee camps, some ad hoc and some established by the Red Cross. Successive Pakistani administrations have proved reluctant to repatriate the majority of the Bihari population. Generations of Biharis have now grown up inside the camps – young people who bear no relation to the events of 1971. Although in the intervening years some Biharis managed to find housing outside the camps and claimed citizenship and thus the chance to assimilate into Bangladeshi society (even if it meant abandoning their Bihari-Urdu identity), those inside the camps remained denuded of their rights.

Almost 300,000 still live in 116 ‘Urdu-speaking settlements’, including the Geneva camp in Mohammadpur, with 25,000 people squeezed into its narrow confines. In 2001, a youth group inside the Geneva camp brought a petition to the High Court demanding voting rights. They won their case and opened the door to a wider court ruling and in 2008 the High Court restored the birth-right of young Biharis as Bangladesh citizens. Despite that victory, as Nazmus Saquib Chowdhury notes, ‘many who grew up in the camps remain socially isolated, under-educated, and are employed mainly in the “informal” sector, still living in substandard conditions without much hope for the future.’

The journalist I spoke to told me that the majority of Biharis just want to ‘restart’, and are reluctant to open ‘old wounds’. However, those Biharis living in Dhaka face a new threat – being forced out of their camps because of the astronomical leap in land prices in the city. In June of last year, a mob attacked the Bihari camp in Kalshi, in the north of the city, setting fire to houses and killing nine members of one family – women and children who were burnt alive after their door was barricaded from the outside. Local Biharis accused the police of helping the attackers, who were drawn from local slum areas, and of shooting dead a 35-year-old Bihari man during the disturbance. Although the pretext for the assault was a confrontation between Bihari and local youth, Abdur Jabbar Khan, chief of Stranded Pakistanis General Repatriation Committee (SPGRC), told newspapers that the attack had been pre-planned to drive the Biharis away. ‘This incident is not new for us. Following the construction of Kalshi Road, the price of land has shot up. A vested quarter has been trying to grab the camp’s land…Those, who do politics and have anti-social elements, goons and arms, planned this all. This is not the result of a Bihari-Bengali feud.’ Arson attacks are not confined to the Bihari camps, they are an increasingly common tactic used by politicians and connected business interests to clear people off valuable land.

Those ‘who do politics’ seem to have the upper hand when it comes to controlling the flow of media stories to the Bangladeshi people, and how events, historical and contemporary, are reported and interpreted. The Bangladeshi journalist (who did not want me to give his name) told me that he was alarmed by the way in which the press had been bought off by political and commercial interests. This is of course the situation the world over, but perhaps it has a greater impact on what is a young nation, trying to come to terms both with its past and a true picture of where exactly it is going. The journalist sketched out to me how the juggernaut of economic growth often turns those who find themselves in its path into enemies of national progress, whether that be people highlighting environmental issues, labour activists, the Biharis clinging onto their slum dwellings or those highlighting corruption and human rights abuses. The journalist told me that a colleague of his, working for a Bangladeshi newspaper, had boasted to him of his cosy relationship with the powers-that-be and then flashed him the Rolex watch gifted to him by a government official. He also pointed out how one of Bangladeshi’s biggest newspapers, the Daily Star, had signed a deal with the powerful lobby group, the Bangladesh Garment Manufacturers and Exporters Association (BGMEA), to promote its activities. In January 2016, the Daily Star signed a Memorandum of Understanding with the BGMEA at the paper’s Dhaka headquarters – an event reported by the newspaper under the headline ‘BGMEA signs deal with Daily Star to devise ways to boost exports’. The article suggested that the Bangladeshi garment industry wanted to rival the Chinese market by reaching a $50-billion export target by 2021. The editor and publisher of the Daily Star Mahfuz Anam was quoted in his own newspaper urging ‘media outlets to extensively cover garment-related issues so that the barriers to business are removed. The entrepreneurs in the garment sector have been playing a leadership role and other sectors are following them. The engine of economic growth is the private sector. This is why The Daily Star has come forward to cooperate with the sector.’ One might ask how this fits with the Star’s published values: ‘The uniqueness of The Daily Star lies in its non-partisan position, in the freedom it enjoys from any influence of political parties or vested groups. Its strength is in taking position of neutrality in conflicts between good and evil, justice and injustice, right and wrong, regardless of positions held by any group or alliance’?

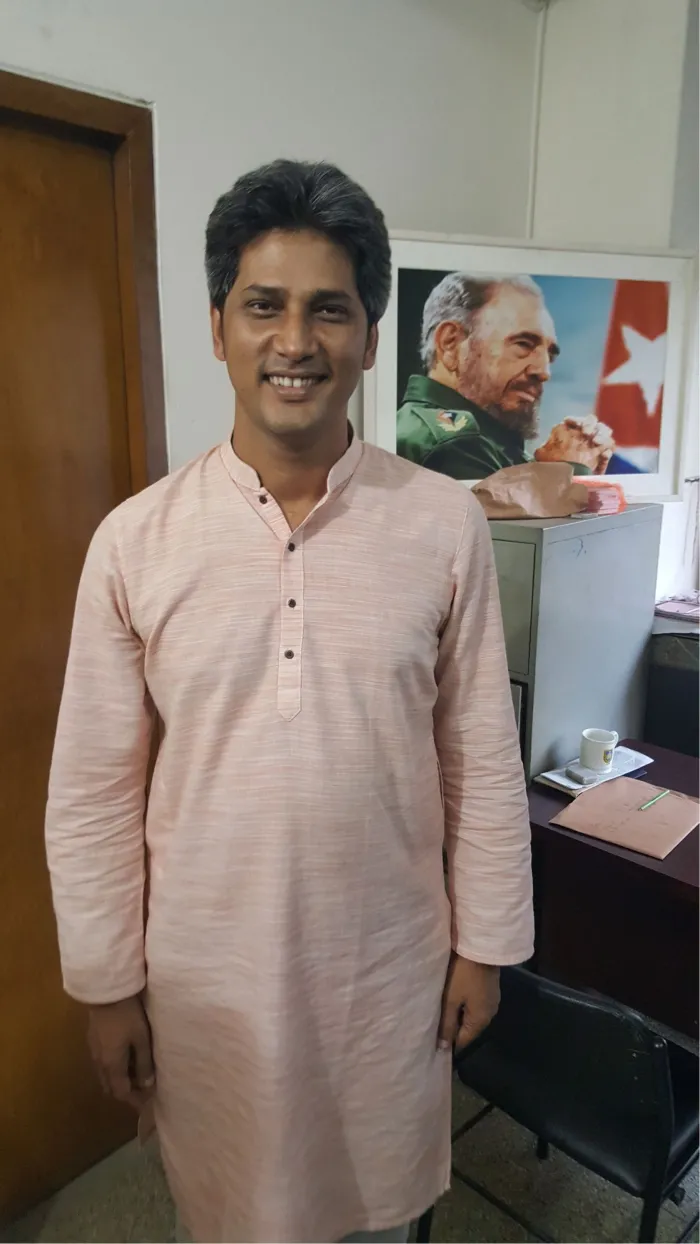

So what of the opposition in Dhaka to this kind of cosy relationship and the wider political cityscape? I went to talk with Zonayed Saki, the high-profile left-wing politician who had run for mayor of Dhaka North in 2015. His office is located inside a commercial building in the centre of Dhaka, and when I arrive I am ushered into his small workplace, and sit at a desk piled high with papers. Saki is very busy and clearly tired, but polite and engaging. He has a youthful look about him, although the former student leader’s hair is now flecked with grey. Saki first rose to prominence as an activist at a time when Bangladesh was under the military rule of General Hussain Muhammad Ershad. He became president of the Bangladesh Students Federation in 1998 and was in the leadership of the movement that toppled Ershad the following year. He tells me, ‘I was 17 at the time. It was a very popular movement, the biggest since 1971, and it was a democratic movement against the military regime. Ershad was ousted through a people’s uprising, mainly based in the city areas. It started when police killed a student activist, Naziruddin Jehad. Under the pressure of the students’ movement the political forces aligned against the regime.’

Although the 1990 uprising was Saki’s political baptism, he tells me that it was during the aftermath that his political consciousness developed. Although no two historical events are the same, as in 1971, he realised that the Left had led the struggle, only to find their democratic demands pushed aside as the political establishment grabbed the reins of power. As he put it to me, ‘we discovered that the system as a whole that Ershad had been sitting on was still intact.’ The ‘plunderers’ were still in place, and continued to use the state machine to extract vast wealth. The basic demands for the separation of powers between the legislature and the judiciary were not carried through. He also points out to me that the constitution does not even allow for parliamentary dissent – so if for example an MP, wishing to represent his constituency over a particular issue, wants to vote against a government bill he has to resign not just the party whip, but his parliamentary seat. ‘You can’t even raise your hand against the prime minister,’ he says. ‘If you go against her, you are expelled.’ The scrutiny committees in the parliament, such as the ones dealing with corruption and human rights abuses, are under the control of Sheikh Hasina’s ruling Awami Party. ‘This is one-person politics,’ Saki says. He also tells me that the Awami League has used the War Crimes Tribunal to prosecute those who ordered or carried out atrocities on behalf of the Pakistani forces, for party political purposes. As he put it, ‘Sheikh Hasina has used history in the [most] maximum way ever.’

In April 2015 Saki ran for the position of mayor of Dhaka North under the banner of his party Ganasanghati Andolan (People’s Solidarity Movement), of which he is chief coordinator. But he tells me that the election was stolen – the ballot boxes had been stuffed with votes and sealed before election day, and by 11 a.m. on the day itself the polling stations had been ‘captured’ by Awami League activists and shut down. At that point, Saki called on his supporters to boycott the poll, so as not to legitimise what he saw as a crooked result.

So for Saki and Ganasanghati Andolan the first struggle is for fundamental democratic rights, both in terms of the constitution and the right of people to protest and strike (hartal). ‘We have to establish citizens’ dignity,’ he says. ‘At the moment, they have no dignity – they are always being harassed by the state or by corporations. I stood for mayor saying that Dhaka has to be a city that its citizens can participate in, and build its future. I talked about development and planning issues, transportation and public health. We stand for the rights of women, the disabled and gender rights, including transgender. We want cultural and religious freedom – in the spirit of the Liberation War.’

He tells me that ordinary people are scared to protest: ‘They are afraid that if they get on the street they may be shot dead. There is a huge fear, and a frustration that nothing is happening.’

At Dhaka University

A few days later, I go with Mahmudul to spend a day at the University of Dhaka. As I enter the university grounds I spot a small demonstration making its way across the road. It assembles in thirty seconds, the banners go up and the chants start, and thirty seconds later it begins to move. A minute later it is surrounded by police, some with weapons, and a minute later the event is over. I rush across the road just as the marchers are dispersing and ask them what they were protesting over. They seem glad to see someone taking notice and explain they are highlighting the adulteration of food with toxic chemicals. I manage to get them back together for a couple of seconds for a photo before they break up.

Mahmudul walks me around the grounds of the university, pointing out the different faculties, including the science faculty housed in redbrick Curzon Hall, a mishmash of arts and craft and Orientalist design, built at the turn of the last century and named after the then Viceroy of India. We watch the end of a student cricket match (the underdogs were victorious), pass by groups of students chatting under the shade, others cycling between faculties. Everywhere there are visual references to 1971.

It seems all very relaxed. We pick up some of Mahmudul’s friends on the way through. One young men tells me he is very interested in drama, but with what seemed some regret was studying fisheries administration because he was worried about getting a job after graduating. Another is a talented photographer, but studies engineering. Every young person I talked to during my visit, student or otherwise, told me the most pressing issue facing them was finding a job. ‘This is our greatest crisis’ was the phrase I heard most often. Lecturers unsurprisingly report high levels of stress and depression in the student population.

Nearly half of all graduates in Bangladesh are unemployed. According to the World Bank, about 41 per cent of Bangladeshi youth are considered NEET (not in employment, education or training). More than 95 per cent of employed youth are reportedly working in the informal sector, 30 per cent are said to be self-employed and 11 per cent are in unpaid family work. The gender balance is stark, with young women being the majority of NEETs, and 90 per cent of women workers being concentrated in vulnerable employment sectors. A 2013 World Bank report found that ‘eighty per cent of young women are at home and not in the labour force. Two thirds of young women are not in employment education or training (NEET), and two-thirds of school drop outs are women.’

One of my group of students, a young man named Sahad, tells me that there is great competition to get a place at the University of Dhaka and that undergraduates were fortunate that their higher education was largely paid for by the state. What is the state of campus politics, I ask Sahad, considering there are plenty of issues for students to get organising over, and given that the university’s students had played such an important role in the democratic revolts of 1971 and 1990? Sahad himself came from a progressive family background; his late father was a community activist and campaigner. To answer my question, he walks me to a hall used by student union activists. Just as we approach it, we are forced to stand back as a contingent of male students march past us, double-step, in formation, as if they were on an army parade ground. I found the spectacle to be quite menacing. Sahad explains to me that they are from a particular hall of residence and have allegiance to the Bangladesh Chhatra League, the student wing of the ruling party. They have heard that their leader has called a meeting and they are on their way to see him. We get to the building and have a look in on the gathering, some standing around the leadership, others seated in rows, male students in front, female students behind.

It is not just the Awami League that has sought to control student politics through the promise of political, financial and career rewards. All the main parties have in effect militarised their student organisations. An Associated France Press report from 2010, headlined ‘Violent student politics wreck Bangladesh campus life’, reported that ‘all three of Bangladesh’s main political parties have strong student wings, which they fund and allegedly arm with swords and even old guns.’ The article quoted a professor emeritus at the University of Dhaka: ‘There is no idealism, this is about greed. Student political leaders make money from extortion, from selling tenders, they control the student accommodation, the canteen.’ He went onto say, ‘In return for providing a ready reserve of young rioters when needed, the political parties allow their respective student wings to make money from their control of the university education system.’ The article said that student body regarded Chhatra League leaders as ‘gangsters’ and quoted one student who said ‘we must pick sides in order to access basic services’. The student said he only got accommodation when he agreed to join JCD, the student wing of the BNP, but then had to switch to the Chhatra League when it took control of the campus. Battles between rival groups have resulted in many students being murdered on campus, including at the University of Dhaka alone, along with hundreds seriously injured.

It’s difficult to comprehend, particularly since all of the students I have met during my visit have been so open-minded, warm and intelligent; but that is naïve. I realise it’s not about the students themselves, or Bangladeshi young people in general, the vast majority of whom I assume want a peaceful life. It’s a reflection of a wider malaise spread by those in power, or competing for power, who have made violence the way of doing business, and as that violence has permeated through society it has taken on a murderous life of its own. In student life, this violence erupts in the space between the dire situation facing most youth and the potential rewards for those few who are prepared to literally fight their way into the political and economic nexus. Now I begin to understand what Saiful Islam was referring to when he talked of ‘how even on the youth side, politics has become how to profit from the system’.

I sit down for coffee with a female lecturer who wished to remain anonymous. She tells me that in her view the government is involved in ‘a sort of terrorism against us’, in the name of development. ‘They are completely besieging us.’ She mentions flyovers in Dhaka under construction by companies attached to politicians collapsing and killing workers, the network of profiteering leading back to the prime minister’s family, arson attacks on slum dwellers, throwing rural communities off government-owned land where they have been cultivating staple foods and the setting up of unregulated Special Economic Zones invested in by multinationals. ‘The ruling party are so powerful now, they just don’t care’, she says.

I ask her about the legacy of 1971. She sighs. ‘I am pro-1971. That is a very touchy subject for me. The war was won by common people, men and women. That fight had to be won, but it doesn’t make all the other fights irrelevant.’

Citations

Special thanks to Mahmudul Hasan for being my guide and companion during my visit and Muhammad Ahmedullah from the Brick Lane Circle for putting me in touch with his contacts in Dhaka and for advice. Thanks also to Naeem Mohaiemen, Saiful Islam, Nazmus Chowdhury, Farhad Mazhar and Zonayed Saki for their time and to Rupom, Jannati, Shohail and the students and lecturers at the University of Dhaka.

Drik can be found at http://drikimages.com/ and Shahidul Alam’s blog is at www.shahidulnews.com. The muslin project can be found at http://bengalmuslin.com

An article on the World Bank’s report on youth unemployment in Bangladesh can be found at http://www.businesshabit.com/2016/09/educated-unemployed-youth-in-bangladesh.html

An article on the 2014 census on slum dwellers can be found at http://bdnews24.com/bangladesh/2015/06/29/number-of-slum-dwellers-in-bangladesh-increases-by-60.43-percent-in-17-years

Nazmus Saquib Chowdhury’s report Unlimited Dreams in Limited Spaces: Feasibility Study for establishing a community learning centre at Mohammadpur Geneva Camp in Dhaka can be downloaded from his Academia.edu page at http://independent.academia.edu/NAZMUSSAQUIBCHOWDHURY

A report on the arson attack on the Bihari Khalshi camp is at http://archive.dhakatribune.com/crime/2014/jun/15/mirpur-clashes-kill-10-biharis

‘Left for What?’, a political profile of Farhad Mazhar by Naeem Mohaiemen published in 1998 can be found at http://old.himalmag.com/component/content/article/2403-farhad-mazharleft-for-what.html

Information of the Baul tradition is at http://bauliana.blogspot.co.uk The site also includes an article by Farhad Mazhar on Lalon Shah. UBINIG, the alternative NGO set up by Mazhar is at http://ubinig.org

An article on Zonayed Saki by Dr Samia Huq: ‘Zonayed Saki: What could a leftist leader offer Bangladesh today?’ is at https://alalodulal.org/2015/04/08/saki-2/

For more background reading, see Bangladesh: History, Politics, Economy, Society and Culture edited by Mahmudul Huque (The University Press Limited Dhaka, 2016), History of Bangladesh 1905-2005 by Milton Kumar Dev and Md. Abdus Samad (Bishwabidyalaya Prokasoni Dhaka, 2015) and Dhaka: From Mughal Outpost to Metropolis by Golam Rabbani (The University Press Limited, Dhaka 1997).